Intangible assets constitute a major value-driver for multi-national enterprises (MNEs).

This is even more so for companies that rely on valuable intangibles rather than physical assets to generate financial returns.

Intangibles such as patents, design, trademarks (or brands) and copyrights are generally easy to identify, value and transfer and as such attractive for multi-national tax planning structures especially as these rights usually does not have a fixed geographical basis and is highly mobile as a result can be relocated without significant costs.

Many MNEs utilize IP structuring models whereby global or regional legal ownership, funding, maintenance and user rights of intellectual property are separated by design from actual activities and physical location of the intangible assets to operate in such a way that the income derived from intangibles in one location are received in another low (or lower) tax regime. As such IP ownership models have a significant effect on the taxation of MNEs.

Cross-border transfer of IP generally attracts high taxes. However, as IP is intangible in nature and therefore highly mobile with no fix geographical boundary, it is possible to easily move these assets from country to country using planned licensing structures. For example, an MNE can establish a licensing and patent holding company suitably located offshore to acquire, exploit, license or sublicense IP rights for its foreign subsidiaries in other countries. Profits can then be effectively shifted from the foreign subsidiary to the offshore patent owning company where little or no tax is payable on the royalties earned. Fees derived by the licensing and patent holding company from the exploitation of the intellectual property will be either exempt from tax or subject to a low tax rate in the tax-haven jurisdiction. Licensing and patent holding companies can also be used to avoid high withholding taxes that are usually charged on royalties flowing from the country in which they are derived, or can be further reduced by double taxation treaties existing between countries.

Many countries allow for the deductions in respect of expenditure on research and development (R&D) or on the acquisition of IP. As such MNE’s can set up R&D facilities in countries where the best tax advantage can be obtained. As such MNEs can make use of an attractive research infrastructure and generous R&D tax incentives in one country and benefit in another from low tax rates on the income from exploiting intangible assets.

IP tax planning models such as these successfully result in profit shifting which in most instances may lead to base erosion of the tax base.

Early 2013, the Economic Co-Operation and Development (OECD) launched the Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS) project. This project focusses on guidelines to MNEs addressing tax avoidance strategies that exploit gaps and mismatches in tax rules to artificially shift profits to low or no-tax locations. By December 2017, sixty-eight countries signed the Multilateral Convention to Implement Tax Treaty Related Measures (MLI) to prevent BEPS.

The MLI is designed as a mechanism for implementing widespread treaty reform and coordination within the existing network of bilateral double tax treaties – without requiring separate bilateral negotiations between each pair of contracting jurisdictions.

Notably, the BEPS project is not just about changing very complex tax laws, it is also about fundamentally changing the behaviour of MNEs. It changes all that is familiar of IP structuring arrangements, group financing arrangements and group holding company structures. Whereas identifying a favourable tax regime, a treaty network and setting up a few or no employees in that regime was the simple model, this will no longer be possible.

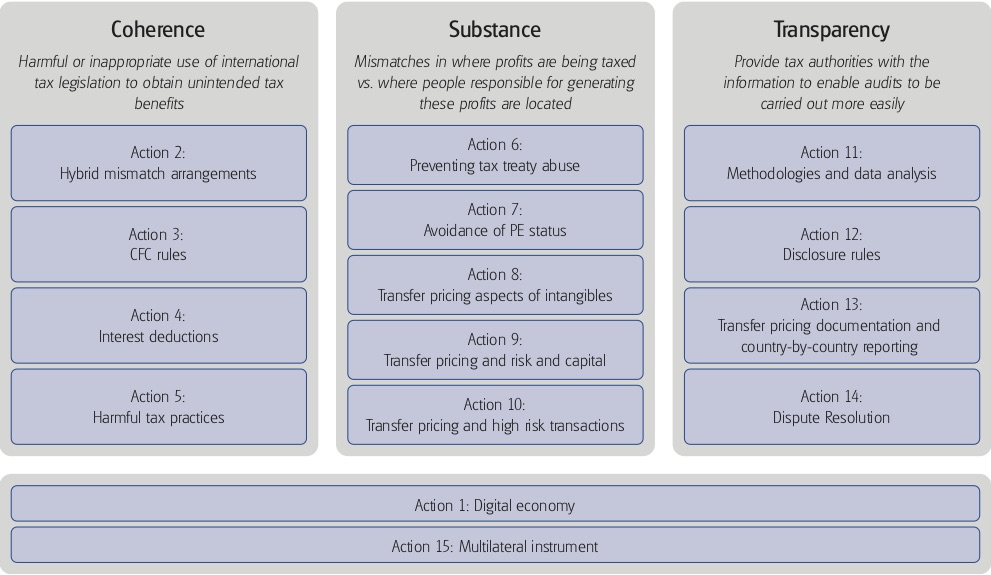

The OECD 15-point Action Plan was announced to address BEPS. Essentially the action plan comprises three main pillars: i.e. Coherence, Substance and Transparency with certain umbrella provisions incorporated into Action Plans 1 and 15.

A central focus of the BEPS Action Plan is to identify and address the impact of corporate tax-structures and it specifically includes IP tax structures. The tax landscape for any group with intangible assets has changed as a result. In this article the key implications for MNEs are briefly discussed.

SOURCE: Vreeswijk J & Tan A-I “The impact of BEPS Action 7 on operating models” in International Tax Review “BEPS Is Broader Than Tax:

Practical Business Implications of BEPS”

IP is a target of three major themes. Coherence looks to tax certain types of low or zero tax income, substance rules look to attribute interact profit to the locations in which key staff are based, and transparency requirements will make businesses highlight low taxed or lightly staffed IP owners. The relevant Action Plans are 8, 10 and 13 that concern transfer pricing, IP Management and reporting requirements.

| Action 8 | Action 10 | Action 13 |

| Develop rules to prevent BEPS by moving intangibles among group members. This will involve: (i) adopting a broad and clearly delineated definition of intangibles; (ii) ensuring that profits associated with the transfer and use of intangibles are appropriately allocated in accordance with (rather than divorced from) value creation; (iii) developing transfer pricing rules or special measures for transfers of hard-to-value intangibles; and (iv) updating the guidance on cost contribution arrangements. | Develop rules to prevent BEPS by engaging in transactions which would not, or would only very rarely, occur between third parties. This will involve adopting transfer pricing rules or special measures to: (i) clarify the circumstances in which transactions can be recharacterized; (ii) clarify the application of transfer pricing methods, in particular profit splits, in the context of global value chains; and (iii) provide protection against common types of base eroding payments, such as management fees and head office expenses. | Develop rules regarding transfer pricing documentation to enhance transparency for tax administration, taking into consideration the compliance costs for business. The rules to be developed will include a requirement that MNE’s provide all relevant governments with needed information on their global allocation of the income, economic activity and taxes paid among countries according to a common template. |

In the case of MNEs operating in different countries, subject to different laws, it is possible to manipulate profits so that they appear lower in a country with higher tax rates and higher in a country with lower tax rates. Action Plan 8 tries to correct the arising imbalance, as it brings out how misallocation of profits generated by valuable intangibles has contributed to BEPS.

Transfer pricing is generally defined as the price charged by one member of MNE to another member of the same organization (related entities) for the provision of goods or services or the use of a property, including intangible property.

The OECD further proposed guidelines for transfer pricing rules to ensure that operational profits are allocated to economic activities which generate them, it includes recommendations on how enterprises should apply the “arm’s length principle” that is, the international consensus on how cross-border transactions between related parties/entities should be valued for income tax purposes. Updated Transfer Pricing Guidelines for MNEs and Tax Administrations were published in 2017 and included in Chapter VI Special considerations for intangibles. The 2017 edition mainly reflects a consolidation of the changes resulting from the BEPS project and incorporates many revisions of the 2010 edition into a single publication.

Intangibles, for the purpose of transfer pricing, are broadly defined in the OECD “….something which is not a physical asset or a financial asset, which is capable of being owned or controlled for use in commercial activities, and whose use or transfer would be compensated had it occurred in a transaction between independent parties” and the following categories are included: Patents; know-how and trade secrets; trademarks, trade names and brands; user rights under contracts and government licenses; licenses and goodwill.

Chapter VI of the OECD Transfer Pricing Guidelines are structured into four sections: 1. Identifying intangibles and their categories; 2. Legal ownership of intangibles and transactions involving the development, enhancement, maintenance, protection and exploitation of intangibles; 3. Transactions involving the use or transfer of intangibles and proper characterization thereof; and 4. Supplemental guidance for determining arm’s length conditions in cases involving intangibles which will include identifying the parties performing functions, using assets, and assuming risks related to developing, enhancing, maintaining and protecting the intangibles by means of functional analysis

To be BEPS compliant, MNEs must be able to recognize the value of intangible assets. It will be necessary to conduct an in depth functional and economic analyses of intangibles to be able to identify transactions involving intangibles and their value to be able to qualify and quantify arm’s length prices for transactions involving intangibles across the business value chain(s), specifically for the DEMPE functions, i.e. development, enhancement, maintenance, protection and exploitation of intangibles.

This assumes well versed knowledge of intangibles and it is advisable that businesses have the appropriate skill base and expertise for IP Management from a BEPS perspective.

It will be important that inter-company agreements properly reflect the underlying transactions. This is to ensure that the profits arising from an activity are appropriately allocated to the various parts in the value chain. Cross functional teams comprising treasury, finance and tax, accounting, procurement, intellectual property and legal departments will be essential for the business to properly understand how stakeholders interact. It is advisable to centralise these functions into a unit for “BEPS compliance”. Close assessment and scrutiny of substance and form of transactions within the business will be necessary to ensure the necessary nexus exists, e.g. appropriate substance and autonomy to support the profits and intra-group charges.

The OECD guidelines provide clarification on the determination of arm’s-length conditions for transactions that involve the use or transfer of intangibles and the parts dealing with ownership of intangibles and transactions involving DEMPE functions. The guidelines stipulate that the return ultimately retained by or attributed to the legal owner depends upon the functions it performs, the assets it uses, and the risks it assumes and upon the contributions made by other MNE group members through their functions performed, assets used, and risks assumed such that the profits arising from intangibles is aligned with the activities undertaken in relation to those intangibles.

On 23 May 2017, the OECD released a discussion draft on the implementation guidance on hard-to-value intangibles (HTVI) in relation to BEPS Action 8.

The Final Report on Actions 8-10 of the BEPS Action Plan (“Aligning Transfer Pricing Outcomes with Value Creation”) mandated the development of guidance on the implementation of the approach to pricing hard-to-value intangibles (“HTVI”) contained in Section D.4 of Chapter VI of the Transfer Pricing Guidelines.

The term HTVI is defined as covering “intangibles or rights to intangibles for which at the time of their transfer between associated enterprises, (i) no reliable comparable exist, and (ii) at the time the transactions was entered into the projections of future cash flows or income expected to be derived from the transferred intangible, or the assumptions used in valuing the intangible are highly uncertain, making it difficult to predict the level of ultimate success of the intangible at the time of the transfer.”

Paragraph 6.190 clarifies that transactions involving the transfer or the use of HTVI may exhibit one or more of the following features; the intangible is only partially developed at the time of the transfer; is not expected to be exploited commercially until several years following the transaction; does not itself fall within the definition of HTVI but is integral to the development or enhancement of other intangibles which fall within that definition of HTVI; is expected to be exploited in a manner that is novel at the time of the transfer and the absence of a track record of development or exploitation of similar intangibles makes projections highly uncertain; has been transferred to a related party for a lump sum payment or is either used in connection with or developed under a co-development agreement or similar arrangement.

As it may be difficult to establish or verify which developments or events may be relevant to the pricing of a transaction involving transfer of intangibles or rights to intangibles, the assessment of which requires specialized knowledge, expertise and insight into the business environment in which the intangibles are exploited. New factors that may be important in the comparability analysis of intangibles are e. exclusivity, extent and duration of legal protection, geographic scope, useful life, stage of development, rights to enhancements, revisions and updates, expectation of future benefit and comparison of risk.

In conclusion it will be necessary for MNE’s to align transfer pricing outcomes with value creation. Specifically, MNEs should either reset transfer pricing policies to allocate profits to (higher tax) territories in which the economically significant activities take place, or redesign their operating models to align economically significant decision-making and control functions with IP ownership.

Enterprises should be able to produce appropriate transfer pricing documentation and comply with country-by-country reporting. Arm’s length conditions for the use or transfer of intangibles would require performing a functional and economical comparability analyses based on identifying the intangibles (inclusive of legal vs actual ownership) and associated risks in contractual arrangements supplemented by examination of actual conduct based on functions performed, assets use, risk assumed.

NOTE: This article first appeared in IPBriefs 2018 vol 1.