All is fair in love and (patent) war, but apparently not when it comes to awarding damages in patent litigation. After nearly 18 months of protracted trench-warfare between Apple and Samsung’s formidable IP legal teams in the Northern District Court of California, Judge Lucy Koh surrendered the matter to a panel of 9 laymen (and women). A mere 22 hours later the (well rested and fed) jury had finished studying Judge Koh’s 109 page instructions and 26 pages of the parties’ juror forms, answered all 56 factual and legal questions and ticked all of the 250+ boxes of the baffling verdict form. In doing so the jury managed to adjudicate on more than 700 legal arguments and delivered 30 different judgments.

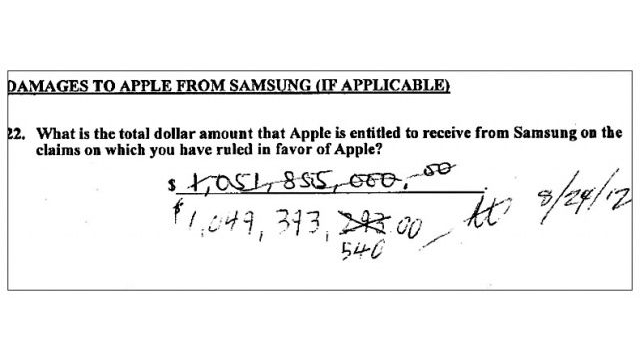

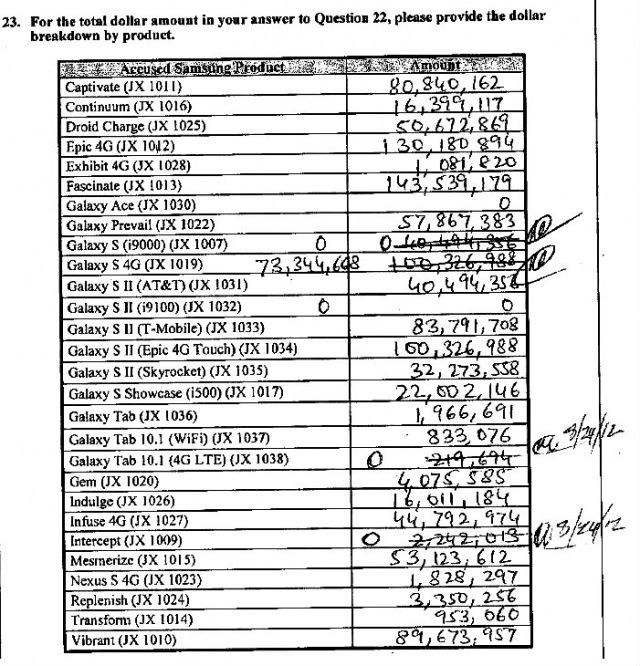

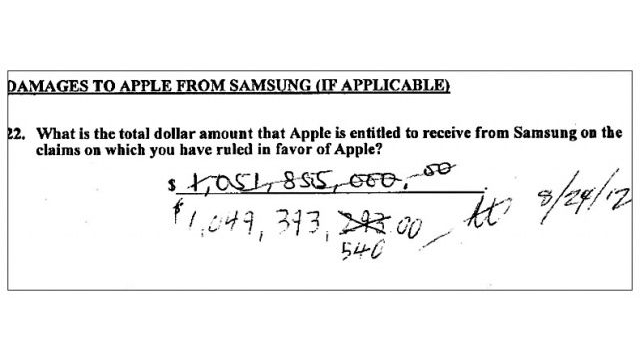

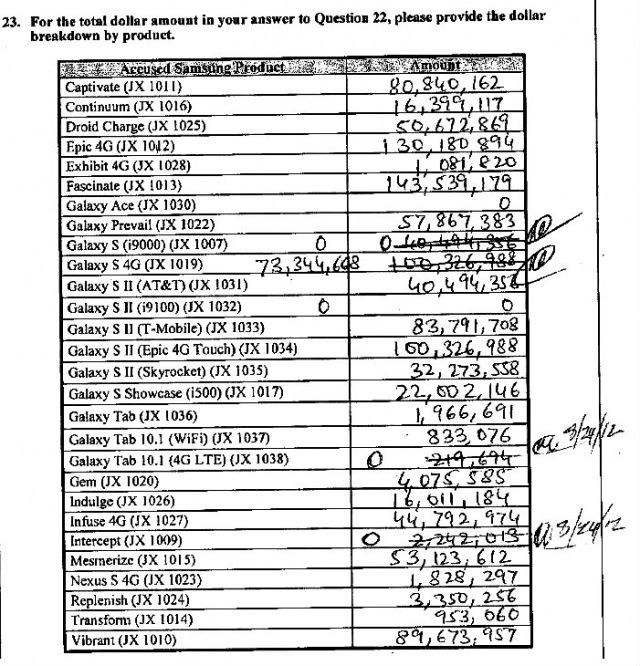

The result? An astonishing landslide victory for Apple and a simultaneous award of damages set precisely at $1 051 855 000.00 (R 8 613 000 000.00). Not to be outdone in skill or efficiency, Judge Koh noticed a minor error in calculation, after which Samsung received a 0.24% discount. The final number: $1 049 343 540.00 (R 8 597 000 000.00).

Which begs the question: how did the jury arrive at this precise figure? And better yet: how is it possible to make such a finding so quickly?

Which begs the question: how did the jury arrive at this precise figure? And better yet: how is it possible to make such a finding so quickly?

Patent law is, by far, the highest specialisation in law that is practiced by only the very brightest of legal-technical minds. For that reason, the lowliest of patent attorney must hold both an LLB and BEng, BSc or other technical degree, complete his/her articles and a further four years of patent training before admission. As a result, the US Patent and Trademark Office is said to contain the greatest concentration of the smartest people in the world.

Therefore, to arrive at this expeditious verdict, the jury in this case must have been composed of nine (very) expert individuals. Or so you might think.

In fact, the jury contained only two engineers and four office workers from technology companies. According to the jury foreman, Velvin Hogan (50), the 20-year old member of the jury “provided most of the debate”. Of the nine members, only 7 hold any college degree while two members are from the Philippines and one from India. According to a study by CNet, two members of the jury are unemployed while the others are occupied as a bike-shop manager, an electrical engineer, a municipal worker, a human-resources consultant, a marketing executive, a social worker, and a network-operations employee. In addition, only one member of the jury owned an iPhone, while none of the members owned a Samsung smartphone.

When asked why she is considering buying an iPad, one female member of the jury said; “I love the technology. I mean, you could sit around in the yard and play with it. Apple comes out with really, really nice stuff.”

Therefore, clearly the jury did not arrive at its decision so quickly by applying their expertise. Which suggests that perhaps the case was not quite as difficult to decide.

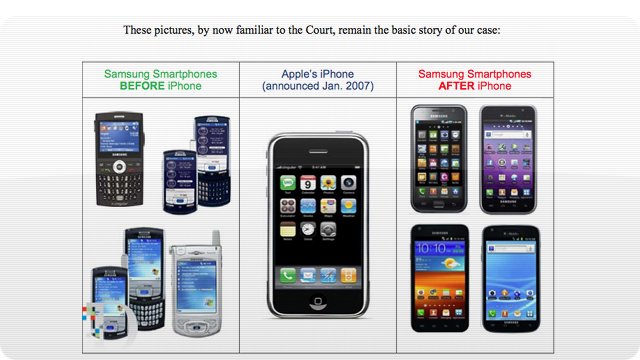

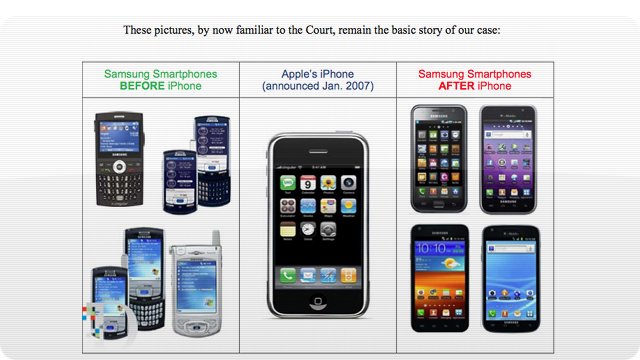

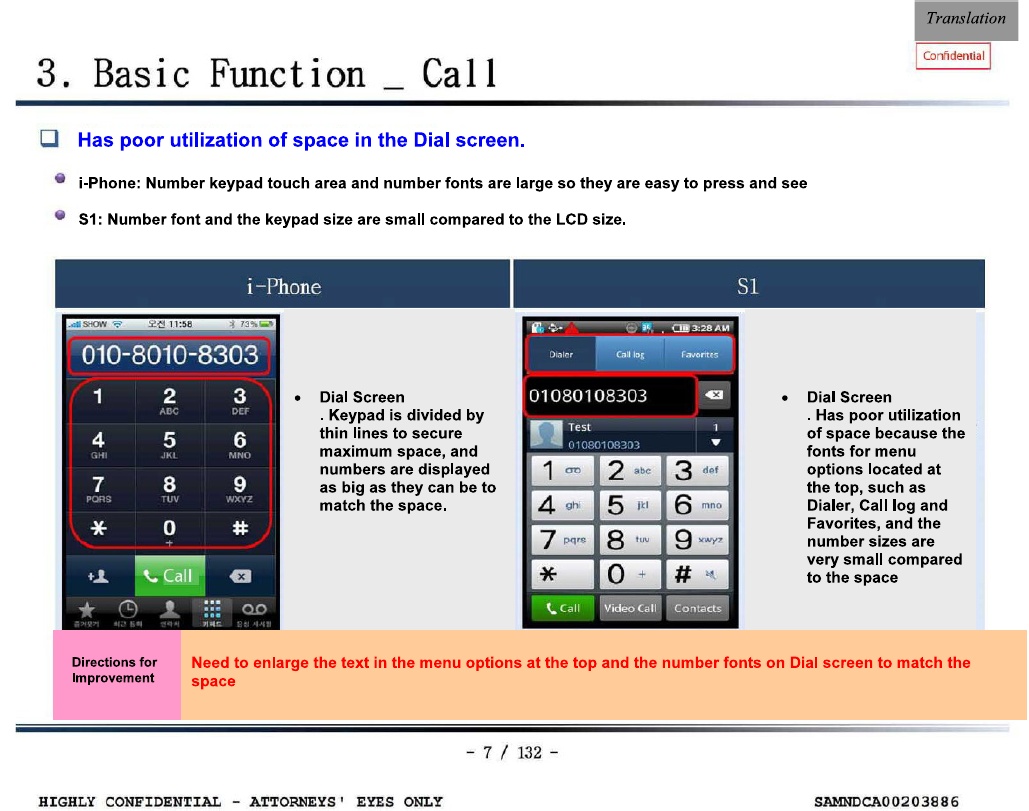

According to the jury, the video clips (illustrating the operation of the disputed patents on both parties’ devices), Samsung’s damning internal communications and a side-by-side comparison of the devices were instrumental to their findings.

However, in addition to a series of software and design patent disputes, Apple’s case also included claims of federal false designation of origin or trade dress dilution (based on the visual similarity between the products), federal and common law trademark infringement, federal and state unfair (unlawful) competition and unjust (unjustified) enrichment.

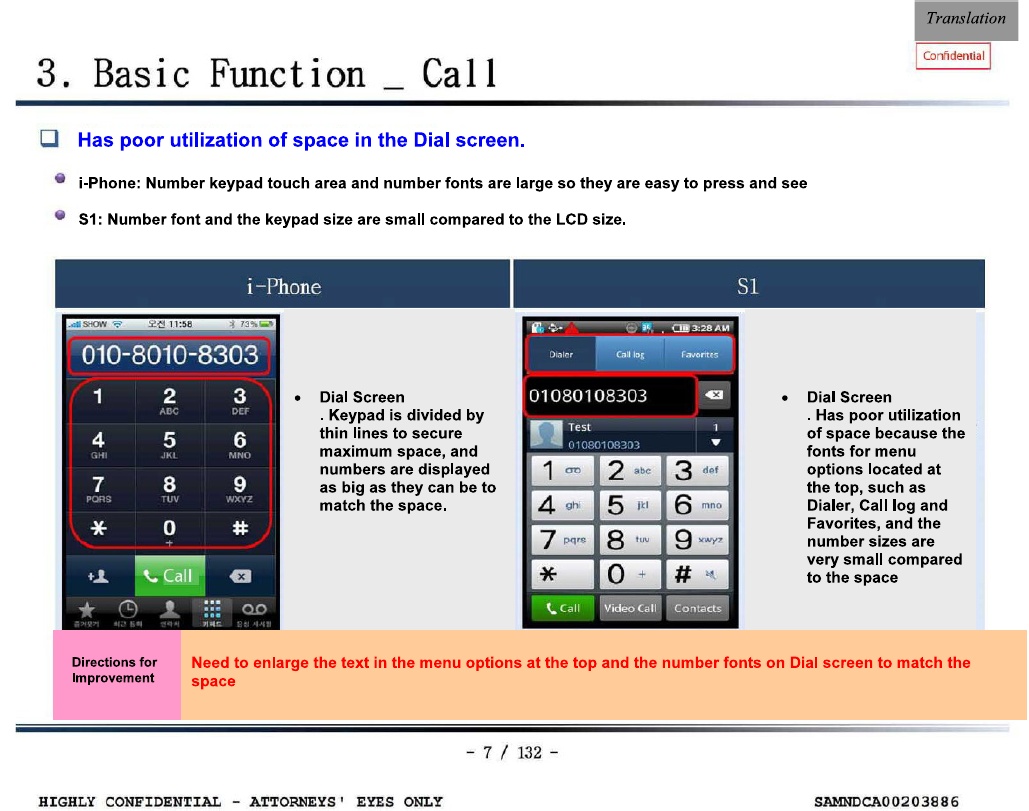

According to the jury, the plaintiff’s reports (Exhibits 44 and 46) were of fundamental importance to their deliberations. The first, a 132 page confidential internal report of Samsung’s Product Engineering Team, contains hundreds of side-by-side comparisons between a Samsung smartphone and an iPhone, each of which examines the operation, design, look and feel of a particular function followed by comments. The second, a 94 page confidential internal document entitled Usability Evaluation Results, contain further direct comparisons along with suggested improvements such as to “provide a layout similar to that of iPhone” or “provide a fun visual effect” identical to that of the iPhone. In total, these documents request more than 200 visual, functional, design and aesthetic changes to Samsung’s products in order to “move it closer” to the iPhone, according to the contents of internal emails from Samsung executives.

Therefore, there is no doubt that on the merits of the case the jury returned the correct verdict. However, the same cannot be said for the award of damages.

According to the jury foreman, at the start of their deliberations the jury’s mood was in favour of dismissal (a verdict in favour of Samsung to dismiss the infringement suit). However, shortly thereafter this changed (presumably with aid of the wunderkind-member’s expert guidance) and the jury began studying the volume of financial statements, actual, hypothetical and projected sales figures, market share indicators, product penetration statistics and the myriad of other documents upon which Apple’s claim for damages, reasonable royalties and punitive damages were based.

This was done, according to Hogan, in what sounds like a conveyor-belt system. Each patent claim was decided individually with regard to each of the (numerous) Samsung products, a finding made and an amount of damages distilled from the financial evidence and testimony. Wash, rinse and repeat 300 times (10 patents, 30 devices).

It might sound simple, but it is definitely not. Patent damages are awarded (theoretically) according to the sum-formula approach. Basically this is a complex version of the negative damages method, which compares the plaintiff’s current patrimonial position with the hypothetical position had the infringement not occurred. However, under South African law (where, of course, a judge quantifies the damages), the positive damages method is also applied after an enquiry into the damages has been ordered and delivered.

Thereafter the court is also required to consider the actual financial value of the patent itself (a calculation that is notoriously difficult to make) by considering a wide range of factors including the patent-holder’s subjective position, the market value of the patent and its current and future application.

In addition, in all IP matters an award for reasonable royalties (in addition to or as an alternative to damages) may be ordered. In this case, the amount is calculated according to the license fees the respondent would have been obliged to pay in order to make legitimate use of the patent to the extent of the actual use in that particular case.

At this point, even the hardiest of mathematician’s head would be spinning. But not so for the Apple v Samsung jury – not only did they manage to make sense of the evidence and complete all 300 calculations in time, but they also had no trouble in determining the amount of damages/royalties for Apple’s additional claims of trade dress dilution. Unfortunately, the jury’s assembly line system suffered a momentary software glitch. As a result, their first verdict included an award of $2 million in damages for inducement while finding Samsung not liable for any inducement – hence the 0.24% discount.

Sadly, while completing its monkey-puzzle template verdict form, the jury was not required to show their calculations. Although this makes for a good surprise and pleases the American sense for well-scripted dramatics, it leaves the rest of the IP community baffled. It is therefore not surprising that this verdict seems like an emotive, large-scale, orchestrated exercise at thumb sucking.

Of course this is unfortunate – while indulging their love of the philosophical “jury of your peers” idea, the US court has blown a gaping hole in an otherwise sound judgment. America is the undisputed world leader in the development of patent law to new technologies but, if this case is anything to go by, also the most backward jurisdiction in IP litigation. Indeed, one almost feels sorry for Samsung, almost.

And after the dust has settled over the battlefield, only one thing remains standing – the unimpeachable authority of the jury. And this is NOT a good thing.

The mobile patent war is far from over. In fact, Apple and Samsung are currently embroiled in more than 50 lawsuits in more than 10 countries. However, except for the United States and Canada, in all of the other jurisdictions where Apple is seeking a repeat performance the jury system in civil cases has either been abandoned or never applied.

Therefore, the fact that Apple’s first notable victory in this battle was won before a jury is no more likely to aid its foreign battles than the US’s skill at international diplomacy is likely to prevent war.

In fact, it is far more likely that cooler heads will prevail outside of the US and that the speed (and arbitrary quantification of damages) in this case will give foreign courts reason to deliver an adverse judgment, or at least a far lower amount of damages. Unfortunately, a court’s finding directly influences the value of a patent in the mobile market and a lower calculation of damages will, in Apple’s case, lower the value of its patents and, concurrently, the company’s market value.

Meanwhile, in South Korea (Samsung’s home market) the court found that Apple was infringing two of Samsung’s patents while Samsung was infringing one of Apple’s patents. As a result, it imposed a national sales ban on Apple’s iPhone 3GS, iPhone 4, the iPad and the iPad 2.

And then, less than a week after Apple announced its newest creation (the iPhone 5) Samsung announced that it is preparing to sue Apple for use of the LTE (long term evolution connectivity) patent technology in the new iPhone. However, Samsung is not planning to use their home-ground advantage in South Korea, but will take the fight to Apple in Europe and the USA.

Clearly, this is not the last we will hear from these trigger-happy giants of the mobile industry. And there is a good chance of an appeal in the US (also before a jury). One may only hope that before then a more transparent judgment will be delivered elsewhere so that we might learn more about the law and less about the lives of nine (very) ordinary Americans.

Cobus Jooste

PS: No, Samsung did not pay Apple $1 billion in nickels (300 truckloads) as rumour would have it. Payment is not yet due pending the judge’s order (which may very well be higher).