Prof Sadulla Karjiker and Dr Madelein Kleyn recently submitted the following comments to the DTI on the Draft IP Policy Phase 1 2017.

The full text of the IP Chair’s commentary may be downloaded here.

Introduction

The Department of Trade and Industry published the Draft Intellectual Property Policy of the Republic of South Africa Phase I 2017 (the “2017 Draft IP Policy”).[1] The Minister of Trade and Industry, Rob Davies, has invited interested persons to submit written comments on the 2017 Draft IP Policy by 17 November 2017,[2] and these comments are submitted in response to that invitation.

We can only bemoan the poor quality of the 2017 Draft IP Policy. Unfortunately, this does not come as a surprise, given previous experience in relation to draft legislation (such as, the Copyright Amendment Bill 2017[3]) and the previous policy document[4] issued by the Minister of Trade and Industry (DTI) in recent years. The 2017 Draft IP Policy is, again, not an exemplary draft document. As a document which should presumably have been drafted with the assistance of legal experts, it even falls short of the standard required of a good undergraduate written assignment.

It makes sweeping statements to support an argument, with no references to the source material to substantiate those statements. For example, there is reference to a study by a “leading South African university” which “found that a significant number of patents granted in South Africa would not pass muster under an examining system.”[5] It also states that there are “major drawbacks” concerning our depository system of patenting, which has been the subject of “numerous studies.”[6]

There is no further information as to the particular studies or any references to any documents which the reader could consult to verify the basis for the statements, or examine the quality of the underlying research which is being cited as support for the particular contentions. Further on, the 2017 Draft IP Policy claims that the economic literature “reveals an inconclusive link between increased IP protection and economic development”.[7]

There are no references to any of the literature which either support a strong link between strong IP protection and economic development, or which may challenge that argument.

Perhaps it is because of this lack of proper support and coherence that the 2017 Draft IP Policy has to resort to the type of language which is more reminiscent of matters which are to be accepted as articles of faith, rather than coherent, evidence-based arguments. Thus, we are required to “verily” accept that our domestic context is so materially different as to depart from the laws which may exist elsewhere.[8]

If this is the type of “evidence-based South African perspective” upon which we are to build our intellectual property law, as claimed in the 2017 Draft IP Policy, it does not bode well for the future.[9] When policy documents engage in unsubstantiated claims, it leaves one with a distinct concern that they are not part of a deliberative, evidence-based exercise, but simply meant to provide a veneer of formal validity, or justification, to implement a particular course of action.

In addition, the 2017 Draft IP Policy lacks coherence and seeks to deal with various issues, but fails to adequately address any of them. For example, besides the issue of pharmaceutical patents, it also touches on the role of IP in stimulating an economy based on innovation (particularly small, medium and micro-enterprises (SMMEs)), competition law and IP, the export of pharmaceuticals, and the protection for traditional knowledge.[10] Most of the statements in relation to the other issues are of such a general nature that no meaningful comment can be given in response thereto.

The key objectives of the 2017 Draft IP Policy are defined as striking a balance between the rights of the IP holder and the users, bearing in mind the South African Constitution[11]. The strategy statement set as an objective the protection of public interest in the health sector and explains that the IP Policy will be addressed in various phases.[12] Phase I of the 2017 Draft IP Policy focusses on patents, with specific emphasis on pharmaceutical patents and access to the public health sector.[13] A mere brief reference is made to other forms of IP, in a passing gesture of these rights, and recent draft legislation and overall IP Policy alignment is not addressed.[14]

The 2017 Draft IP Policy also announces the establishment of the Inter-Ministerial Committee on Intellectual Property (IMCIP), which, although commendable, unfortunately is intended to focus, for the time being, on public health and access to medicine.[15] One would hope that such a body could serve the purpose of focussing on IP, as a whole, and develop a policy that is not discriminatory with regards to a particular IP type, subject matter and technology industry. Also, the composition of the IMCIP should include industry and private practice specialists, and should not be confined solely ministerial and administrative staff, or the critics of IP, as currently appears to be the case with the proposals coming from the DTI.

In addition, it is important that an effective, and expert, Standing Advisory Committee on Intellectual Property Law Rights (SACIP) pursuant to section 40 of the Copyright Act be re-established (given the fact that it appears to have become ineffective). As was the case in the past, legislative initiatives in the area of IP should start with the SACIP.

Patent system

The focus of the 2017 Draft IP Policy appears to be our current patent system. More specifically, the reason for the patent system being the focus of immediate legislative attention is the contention that it is an obstacle to public health.[16] The 2017 Draft IP Policy claims that a “substantial part of the problem” in relation to public health is a consequence of the fact that South Africa does not conduct substantive examination of patents, but operates a so-called “depository system” in relation to patent applications.[17] While it is not suggested, as a matter of fact, that a depository system may not present an opportunity for abuse of the patent system, the 2017 Draft IP Policy does not present convincing evidence for the contention that there is a substantial problem.

On the contrary, there may be good reasons why the problem may not be as significant as it is claimed to be. Again, the following counter arguments are not stated as matters of fact, but these are possibilities which a well-researched policy document should have considered. There is no suggestion of that having been the case.

First, the primary reason why we do not subject patent applications to substantive examination is as a result of the lack of capacity to operate an effective system of substantive examination. We simply do not have enough people with the required technical expertise to operate such a system. This reality is — to some extent — acknowledged in the 2017 Draft IP Policy.[18] To put the scale of the problem in context, according to a recent enquiry at the South African Institute of Intellectual Property Law, there are currently, in total, approximately 124 registered patent attorneys in South Africa. In contrast, the German Patent Office, on its own, has approximately 800 patent examiners.

Second, the 2017 Draft IP Policy seeks to support its argument by relying on a study which suggests that South Africa grants patents at a much higher rate than other countries.[19] That fact on its own does not suggest that there is a systemic problem with the depository system, or, more specifically, with pharmaceutical patenting. In comparison to countries such as the US, Europe, India and Brazil, the number of applications in South Africa is hardly significant.[20] Furthermore, most of the South African patent applications are foreign applications or PCT national validation, that is, the first filing for the patent was in a country other than South Africa. This may be suggestive of two facts: that the South African market is generally not considered to be commercially significant enough to bother with seeking patent protection in respect of patents which have been filed elsewhere; and, therefore, that only patent applications with real prospects of success elsewhere (or those that are valuable) are protected in South Africa.

Third, there is the possibility that the patent profession, mindful of the fact that South Africa has a depository system, has to ensure that, as a matter of best practice, it conducts a more rigorous exercise (or no less comprehensive assessment than counterparts elsewhere) in ensuring substantive compliance, and validity. Their clients will look to them if they have failed to ensure that their inventions received the required legal protection, rather than they (i.e., the patent professionals) being able to deflect (or apportion) blame due to an added level of substantive scrutiny by patent examiners. In fact, before instituting a patent infringement claim, the relevant attorneys will compare the claims of the registered South African patent that is being sought to be enforced against the corresponding patent filed in leading jurisdictions operating an examining system to ensure that the patent claims are aligned with its foreign corresponding patents and, if necessary, amend the patent claims in an attempt to ensure its validity. Also, given the fact that a patent application includes names of the individual patent attorney and the legal firm for which the attorney works, there is a reputational risk for the attorney and the firm should they file frivolous, or clearly invalid, patents. Moreover, in the case of patents emanating from South Africa, it is highly unlikely that an inventor would only seek to patent an invention in South Africa. Given the limited size of the South African market, an inventor would want to ensure that its product is also protected by patent law in the other major markets, such as, the US, Europe and Asia. In other words, patents which have been filed in South Africa may proportionately be of a much higher quality, despite South Africa having a depository system. Thus, for this reason and the previous reason, there may be a selection bias for the filing of good patents applications in South Africa, which may account for the significantly higher success rate of patent applications.

Fourth, it is important not to overstate the benefit of having a substantive-examination system. Substantive examination is not a guarantee that granted patents are valid. While a substantive-examination system will provide an additional level of scrutiny to patent applications, a patent granted under such a system remains open to challenge, particularly in patent-infringement proceedings, when there is a counter-claim of patent invalidity. This is most certainly the case with our depository system. However, rather inexplicably, the proposals in the 2017 Draft IP Policy — which targets the alleged poor quality of the patents being granted in South Africa — actually threaten to considerably dilute the ability to challenge the validity of an invalid patent which has been granted! While its intentions in relation to post-grant opposition procedures are as clear as mud, the 2017 Draft IP Policy proposes, as an interim measure — while the opposition procedures (see our comments below) will be finalised — that all oppositions to the grant of a patent should “proceed by way of administrative review in accordance with the provisions of the Promotion of Administrative Justice Act 3 of 2000 (“PAJA”).”[21] Administrative review proceedings are very limited forms of legal oversight: they have to be brought within the strict time limits prescribed, and are concerned with the reasonableness of decisions, not the correctness of those decisions. Thus, an administrative review is, strictly speaking, not able to resolve the issue of whether a patent should have been granted on the substantive basis of patent law. One would struggle to find many worse examples of proposed legal reform than this misguided proposal. This, once again, displays the concerns which we have concerning the level of legal expertise employed by the DTI when formulating proposals. If there really is a substantial problem with our depository system, the proposal will exacerbate the problem, and not provide a solution to it!

The proposed provision for pre-grant oppositions is, generally, a concern.[22] As already indicated, and as the 2017 Draft IP Policy recognises, there is insufficient expertise to conduct an efficient pre-grant opposition procedure. A pre-grant opposition procedure requires adequate staffing by individuals with the necessary expertise to assess substantive issues of patentability, and not just issues of procedure or administrative law. Furthermore, if pre-grant oppositions are permitted, provision will have to be made for a party to appeal the outcome of a pre-grant opposition.

In our view, provision should only be made for post-grant opposition (or removal) proceedings by third parties. Allowing for formal pre-grant opposition proceedings raises the following concerns: the proceedings may be abused by third parties; delay the examination proceedings (and possible grant of patents); be resource intensive, and in fact be of very little substantive value, given the availability of post-grant opposition proceedings. If anything, the costs which may have to be incurred in defending a patent application, when pre-grant opposition proceedings are instituted by a well-resourced third party (who may seek to frustrate the granting of a patent), may have a disproportionately adverse effect on local inventors, SMMEs and research institutes. The effect could be to dis-incentivise these critical contributors to the country’s technology output. It should be borne in mind that a patent expires 20 years from the date of filing of the application, and there is no provision in South Africa to extend the term thereof for any reason, unlike in many other jurisdictions. The lost time occasioned by an elaborate and lengthy pre-grant opposition system (and appeals which may follow) will negatively impact on the desirability of filing patents in South Africa. During the prosecution process, provision can be made for third parties to make written submissions (including on an anonymous basis) about the state of the prior art concerning a particular patent application. However, this should not be a formal pre-grant opposition procedure.

Fifth, perhaps most significantly, if the 2017 Draft IP Policy is correct about the fact that the South African patents register is clogged with invalid patents, it begs the question as to why we have not seen a significant number of litigation cases involving issues of patent validity as a consequence. The pharmaceutical market is a highly competitive market. It is, arguably, competition which has yielded us the levels of innovation in pharmaceuticals. In fact, to date, there has been no indication of an alternative system which is likely to produce equivalent results.[23] If a competitor is excluded from a potentially lucrative market (because a particular medicine is sold at inflated prices, well beyond its economic value) due to a patent of questionable validity, what do we expect would happen? Unless the pharmaceutical industry as a whole constitutes a cartel (or some other form of cabal), a rational competitor would assess its chances of success in any potential patent-infringement litigation, and, based on those findings, possibly enter the relevant market as a competitor. Not to do so would be the equivalent of leaving money on the table for a rival firm with an invalid patent. There is no suggestion that the levels of patent litigation are high in South Africa. Moreover, the fraudulent assertion of patent rights may also amount to a contravention of competition law, if it amounts to an abuse of dominance on the part of the firm which asserts those rights.[24]

Sixth, if it is the case that any patent (that is, irrespective of whether it was validly granted) is preventing the access to necessary medication, and that this is causing a public-health crisis, our law already provides for ways in which these concerns could be addressed. The Patents Act[25] also provides for the possibility of a compulsory licence where, inter alia, the demand for the patented article in South Africa is not adequately being met on reasonable terms, or because the price of the imported patented article is excessive in relation to the price charged in the country from which it was imported.[26] In addition, the Medicines and Related Substances Act[27] makes provision for the Minister of Health to allow for parallel importation of more affordable medicines.[28] To date, neither of these provisions have been used to address the obstacle which patent law is claimed to represent to public health in South Africa.[29] There is no proof that these provisions have proved to be ineffective, or inadequate, in addressing issue.

The 2017 Draft IP Policy does not address any of these issues, and does not provide a convincing case that our depository system is as problematic as it is claimed to be. For purposes of argument, let us assume that the economic literature is indeed inconclusive about the importance of strong intellectual property law to a knowledge-driven economy (as claimed in the 2017 Draft IP Policy[30]), the rational course of action would not be to go for broke and dilute, or expropriate, the property rights afforded by intellectual property law. One would expect a cautious, prudent approach to such matters, and not plunging in with headlong haste, or reckless disregard for the economic consequences.

There is a real danger that the proposals in relation to the substantive examination of pharmaceutical patents will cause the patenting system to grind to a halt, which — given the already troubling proposed erosions of property right contained in the Copyright Amendment Bill 2017 — could do untold damage to our reputation in relation to the protection of intellectual property. We simply cannot afford to be cavalier about the possible consequences of these types of changes to our legal institutions, such as, intellectual property law. We should not rush into potentially-disastrous experiments, undermining well-established property rights.

In principle, the Chair supports a substantive search and examination patent system for South Africa. A more sensible, and efficient, approach could be a combination of all or some by following possibilities. First, there could an informal “phased in approach” by utilising the expertise being developed in the manner suggested above, that is, to identify invalid patents (not limited to pharmaceutical patents), and to seek their removal. Second, as another interim measure, we could rely on the results of a foreign substantive, as many other countries do, and as we have done to date for PCT applications as receiving office whilst we build up the necessary expert capacity. Third, we could participate in a Patent Prosecution Highway (PPH) programme. We could, initially, simply accept patents granted by another examining jurisdiction.

For completeness, it also necessary to state that the contemplated “two-tier patent system”, namely, an examination system for pharmaceutical patents, and a depositary system for other patents is, to say the least, problematic as it is not clear that such a system would be in conformity of South Africa’s international treaty obligations. Article 27 of the TRIPS Agreement does not permit discriminatory patenting, based on different technologies, and states that “patents shall be available and patent rights enjoyable without discrimination as to the place of invention, the field of technology and whether products are imported or locally produced.” The only relevant consideration to the grant of a patent should be whether the substantive requirements of patentability have been satisfied.

Patentability criteria

The 2017 Draft IP Policy suggests that the “patentability criteria form a part of the Patents Act,”[31] as if this is not already the case (unless, of course, the suggestion is that we should change our patentability criteria). The Act stipulates that the patentability criteria for an invention is that the subject matter of the patent be a “new invention which involves an inventive step and which is capable of being used or applied in trade or industry or agriculture.”[32] Furthermore, subsections 25(9) to (11) of the Act also potentially concern the patentability of pharmaceuticals.

It is the view of the Chair that the exiting criteria set by the Patents Act should not be changed, as it is sufficiently restrictive to prevent frivolous patents. While, in some sense, all innovations are incremental, the fact that an invention has to be non-obvious and new means that only significant advances are patentable. It is important to note that even “incremental” innovations, whether in the pharmaceutical field or in other fields, often require significant investment (for example, clinical trials, product registration, infrastructure, distribution channels, training of medical personnel, education, or creating awareness). As stated previously, we should create the necessary incentives for investors or pharmaceutical companies to establish a pharmaceutical manufacturing capacity in South Africa, and making the patentability criteria more onerous than in the developed countries is unlikely to achieve that goal. Incidentally, while comparisons are sought to be made with countries such as India or China, factors such as the sizes of the potential markets, and educational levels, in those countries make the comparisons inappropriate. We should not be under any illusion that the BRICS countries are a homogenous set of countries. In many ways, they are as different to us as we are to the developed countries, and investors are hardly queuing up to invest in South Africa to the extent that we can be cavalier about eroding property rights.

Disclosure requirements

The Chair is in favour of the proposal in the 2017 Draft IP Policy that patent applicants adequately disclose information regarding the status of similar and related applications filed in other international jurisdictions. However, that obligation should only extend to the disclosure of the prior art disclosed in foreign corresponding patent applications, and not to related inventions, i.e., applications not part of the corresponding patent family. Furthermore, this disclosure requirement should be accompanied by a corresponding right for the applicant to amend its application so as to amend its claims in view of overcoming the cited prior art.

Exceptions (including Bolar– and research-exceptions)

The 2017 Draft IP Policy recognises that, pursuant to section 69A of the Patents Act, South Africa has a so-called Bolar exception, which allows a party, such as a manufacturer of generic medicines, to obtain regulatory approval for a product prior to the expiry of a patent covering the product.

While an arguable case may be made out for the existence of research exception,[33] the Chair supports the inclusion of an explicit exemption in the Patents Act to allow for reasonable technical trial, research and experimental use. However, the connection that the 2017 Draft IP Policy seeks to make between these types of exception and patents which are the consequence of Intellectual Property Rights from Publicly Financed Research and Development Act 51 of 2008 (IPR Act) is unclear.[34] For the avoidance of doubt, there should be no further interference with the commercial rights of patent holders in outside of the IPR Act (and preferably also in respect of commercial rights which have been granted in respect of patents which were the result of process under the IPR Act).

Voluntary licences

There should be no forced disclosure of the details of licence agreements. The terms of patent licences, as with most commercial agreements, are usually confidential between the contracting parties because the parties are keen to avoid giving competitors any information as to any competitive advantages which their particular arrangements may offer. It is not clear what purpose would be served by seeking to compel commercial parties to disclose the details of the terms of their licence agreements. There is no general requirement for parties in commercial transactions to disclose the terms of their agreement.

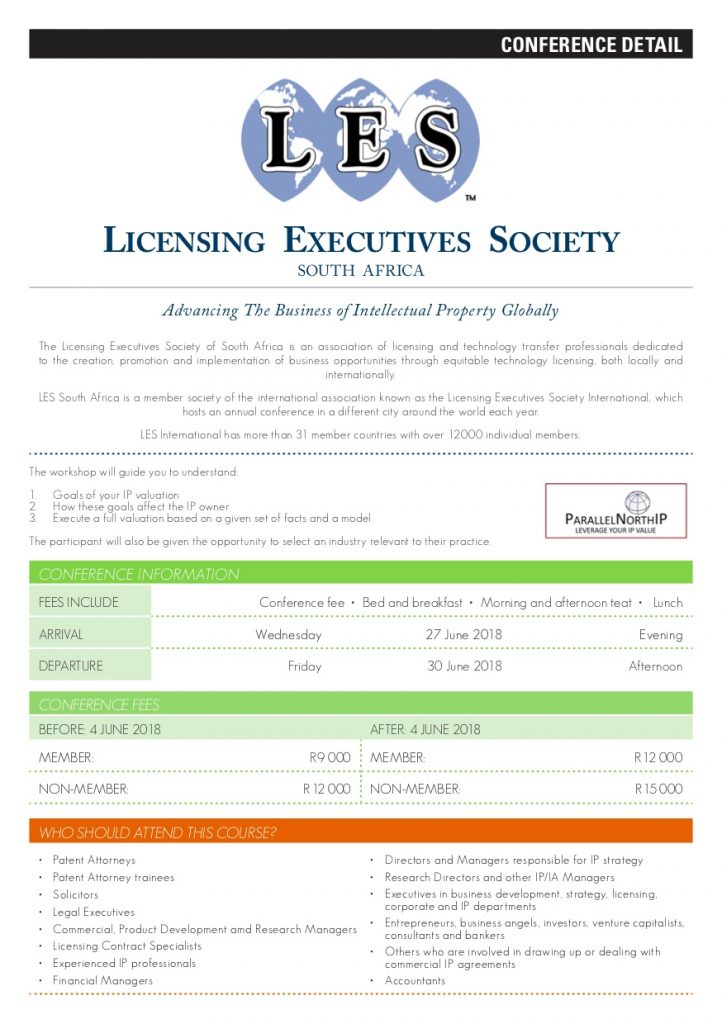

The DTI could seek collaboration with societies such as the Licensing Executives Society (LES) that could assist with guidelines on licences. Perhaps organisations such as the LES may be able to provide anonymised data on licence agreements in the different technical industries, which could provide insights into the costs and practices associated with licensing.

Compulsory licences

As already indicated above, the Patents Act provides for the possibility of a compulsory licence where, inter alia, the demand for the patented article in South Africa is not adequately being met on reasonable terms, or because the price of the imported patented article is excessive in relation to the price charged in the country from which it was imported.[35] While that provision should have been adequate to address concerns about the social costs of access to medicines, the government also amended the Medicines and Related Substances Act to make provision for parallel importation of more affordable medicines.[36] The provisions, arguably, already exceed the flexibilities with respect to compulsory licensing pursuant to Article 31 of the TRIPS Agreement.

The 2017 IP Policy suggests that the current system of compulsory licensing is expensive and subject to unnecessary delays, and that it should be replaced with a less complicated administrative process that excludes a judicial process. The Chair does not support this view or proposal.

The effect of a compulsory licence is the deprivation of (or interference with) the constitutionally-protected property rights of the holder of intellectual property. No such action should be permitted without the owner’s ability to have recourse to the course, if it considers the particular actions to be an unlawful interference with its constitutionally-protected property rights.

Alternatives to the two-tier (or discriminatory) patent system

If there is indeed a proven concern relating to the prevalence of invalid pharmaceutical patents, a more prudent approach — given our severe constraints on the necessary expertise to conduct substantive examination of patents — to address the problem of invalid pharmaceutical patents is to use the expert capacity that is being created in a more focused manner. The DTI could establish a group (or team) within DTI, staffed by these experts, whose function it is to investigate pharmaceutical (or any other) patents, and, if any patents are found to be invalid, they could institute revocation proceedings against the relevant patent holder, if necessary.

Government use

The 2017 Draft IP Policy refers to section 4 of the Patents Act, which provides that the relevant Minister may use an invention for public purposes. Section 4 permits such use on the basis that there is an agreement related to such use, failing which, the State may approach the Commissioner of Patents to determine the conditions of use. The 2017 Draft IP Policy suggests that the TRIPS Agreement does not require prior negotiation and suggests that government will do what it has to do to effect to legislation that will give access to health care and services.[37]

Although engagement with stakeholders is mentioned, the 2017 Draft IP Policy appears to suggest that Article 31(b) of the TRIPS Agreement allows for intrusive legislation. In fact, Article 31(b) only permits such “forced” interference with rights if, prior to such use, the proposed user has made efforts to obtain authorisation from the rights holder on reasonable commercial terms and conditions, and that such efforts have been unsuccessful within a reasonable period of time. In situations of national emergency, or other circumstances of extreme urgency, where the former requirement may be waived, the rights holder must, nevertheless, be notified as soon as reasonably practicable concerning the relevant use.

IP and innovation

As a country, we should not be assuming the role of perennial victim, and continue lamenting the fact that we are a country that lacks a pharmaceutical manufacturing capacity.[38] We should be creating the necessary legal framework that provides the incentives for investors to establish a pharmaceutical manufacturing capacity in South Africa. This is not going to be achieved by scaring away investors with the constant threat of compulsory licences (or “forced” technology transfer). After all, South Africa is, arguably, one of the few African countries with the necessary infrastructure and human potential to conduct research and development, and manufacturing, of pharmaceuticals. We will only make a real breakthrough concerning issues of public health in the long run if we have a pharmaceutical manufacturing capacity.

Furthermore, it should be noted that IP law reform, on its own, will be insufficient to promote a pharmaceutical manufacturing capacity. The regulatory aspects for acquiring the necessary authorisations to manufacture, sell and export, medicines are set by the Medicines Control Council (“MCC”). At present, the approval processes of the MCC take 4-5 years, if not longer. In addition, a manufacturing and production facility must be in place for the MCC approval process, which itself may take 4-5 years to be approved. Government should, thus, ensure that the approval periods are significantly reduced, in order to ensure that approved medicines can get to the market earlier. The earlier medicines can get to the market, the longer the period a patent holder has to recoup its investment during its exclusive period provide by patent protection. This would provide the incentive which patent protection is intended to provide.

It is necessary to hasten to add that we are not insensitive or unsympathetic to the significant issues concerning public health in South Africa. We are not even suggesting that there are absolutely no issues concerning intellectual property law in the area of public health. What we are not prepared to do is simply accept short-sighted, superficial, and uninformed, rhetoric as the basis for decision-making, and the potentially harmful consequences of the changes being sought on that basis. Questions of public health and property rights are not a “one-shot game”. If we are going to implement measures which harm property rights, and the incentives which they provide, we must be aware of the possible long-term consequences of those actions. While it is easy to make an emotive case for access to medicine, it is important to bear in mind that it is only because of the existence of the particular medicines that there can be calls for access. It is important to note that the proprietary rights afforded by patents serve to incentivise future innovation.

Undermining property rights to gain access to existing patent-protected products is short sighted as it will deter future innovation. In other words, by undermining proprietary rights we will simply have to hope that, in the future, incentives exist elsewhere in the world for the innovations, in things like medicine, that we, as Africans, require.

There is a genuine sense of garbled thinking in relation to the suggestions concerning intellectual property law, innovation and the promotion of SMMEs. The 2017 IP Draft Policy suggests that SMMEs need alternative forms of intellectual-property protection, which are less onerous than patents, and it contemplates the introduction of “utility model” protection in South Africa as a possibility.[39] The suggestion is problematic for a few reasons.

First, the 2017 IP Draft Policy does not suggest why our current protection for functional designs under the Designs Act[40] does not already provide the necessary “lesser” form of protection which is thought to be desirable. It does, however, indicate that this issue will be investigated in Phase 2.[41]

Second, if an SMME has something that is patentable, why should it seek any “lesser” form of protection than a patent? In fact, if patent rights are not undermined by the threat of unnecessarily-broad provisions relating to compulsory licenses, SMMEs should be able to use the patents (or the possible grant of patents) in order to attract potential investors. Strong intellectual property rights may be the only significant asset an SMME may have to attract investors, or financing. In other words, intellectual property rights, such as, patents, should provide the rights holders with the required level of protection where they can be considered to be assets in the form of capital.

Third, the fact that we have a depository patent system has, arguably, made it cheaper and easier for SMMEs to obtain patent protection to date. If these costs of patenting are considered to be an obstacle for SMMEs, which government seeks to address, it could provide inventors with financing to cover these costs (and security foreign patent protection). Also, the expert capacity that is being created by DTI could be used to provide a pro bono service to provide SMMEs with the necessary legal expertise to file patent applications.

Fourth, the DTI’s attitude to intellectual property rights appears to be somewhat schizophrenic. On the one hand, it seems to be too eager to undermine intellectual property rights, due to their alleged harmful effects, while, on the other hand, it is prepared to create new forms of intellectual property rights or cram additional matter into the existing framework of protection (such as, traditional knowledge), which does not rightly belong there.

Last, an additional form of intellectual property rights, such as, utility models, will be available to any person, and not just SMMEs. In other words, utility models will not be in any favoured position over large, or multinational, corporations per se.

Copyright

In relation to the issue of copyright law, there appears — almost at the very end of the document — a cryptic note which, in effect, states that the 2017 Draft IP Policy will not deal with copyright law (or indigenous knowledge) because these legislative initiatives have already “commenced or been concluded prior to the formulation of the IP Policy.”[42]

There is no indication that the legislation which has been passed, such as, the disastrous Intellectual Property Laws Amendment Act 28 of 2013 (“IPLAA”), or the Copyright Amendment Bill 2017, are consistent with the policy as set out in the 2017 Draft IP Policy. To be frank, this was probably done because there appears to be no discernible set of principles which are being followed in relation to intellectual property law, other than the erosion of property rights.

Conclusion

As the Chair has previously stated, any initiative to improve South Africa’s intellectual property laws is welcomed. It is disappointing that the focus of Phase I is so limited in scope; essentially, it is confined to pharmaceutical patents and public health. It is hoped that the DTI will produce a far more comprehensive policy and strategy concerning IP, and specific legislative proposals.

Commentary authored by:

Prof S Karjiker

Anton Mostert Chair of Intellectual Property Law

Faculty of Law, Stellenbosch University

Dr MM Kleyn

Fellow of the Anton Mostert Chair of Intellectual Property Law

Faculty of Law, Stellenbosch University

[1] Draft Intellectual Property Policy of the Republic of South Africa Phase I 2017, Notice 636 of 2017 (GG 41064, 25 August 2017).

[2] Initially, the deadline for written comments was 23 October 2017, but was subsequently extended.

[3] Copyright Amendment Bill 2017, version B13-2017, published by the Department of Trade and Industry (“DTI”) on 16 May 2017.

[4] Draft National Policy on Intellectual Property, 2013, General Notice No.918 of 2013, published in the Government Gazette of 4 September 2013.

[5] 2017 Draft IP Policy p 7.

[6] 2017 Draft IP Policy p 15.

[7] 2017 Draft IP Policy p 8.

[8] 2017 Draft IP Policy p 8.

[9] 2017 Draft IP Policy p 32.

[10] 2017 Draft IP Policy pp 5 and 24-5.

[11] Constitution of the Republic of South Africa 1996.

[12] 2017 Draft IP Policy pp 4 and 9-10.

[13] 2017 Draft IP Policy p 4.

[14] 2017 Draft IP Policy p 36.

[15] 2017 Draft IP Policy p 10.

[16] 2017 Draft IP Policy p 6.

[17] 2017 Draft IP Policy p 6.

[18] 2017 Draft IP Policy p 5.

[19] 2017 Draft IP Policy p 6. The depository system applied in South Africa was not the focus of the study, which mentioned the South African system for comparative purposes.

[20] http://www.wipo.int/ipstats/en/statistics/country_profile/ (accessed 29 August 2017).

[21] 2017 Draft IP Policy p 17.

[22] 2017 Draft IP Policy p 16.

[23] McMillan p 31.

[24] van der Merwe A, et al. Law of Intellectual Property Law in South Africa 2ed (2016) p 537-8.

[25] Patents Act 57 of 1978.

[26] Section 56.

[27] Medicines and Related Substances Act 101 of 1965.

[28] Section 15C. Confining the express provision relating to the parallel imports (and facilitating compulsory licences) only in respect of pharmaceutical patents, and not other technologies, arguably, constitutes a contravention of the non-discrimination provision in Article 27 of TRIPS Art 27.

[29] 2017 Draft IP Policy p 6.

[30] 2017 Draft IP Policy p 8.

[31] 2017 Draft IP Policy p 24.

[32] Section 25(1) Patents Act 57 of 1978 (“Patents Act”).

[33] See sections 45 and 55 Patents Act. Section 45, arguably, serves to protect the commercial exploitation of an invention only. Technically, section 55 provides for a compulsory licence for a dependent invention of considerable economic significance.

[34] 2017 Draft IP Policy p 22.

[35] Section 56 Patents Act.

[36] Section 15C. Confining the express provision relating to the parallel imports (and facilitating compulsory licences) only in respect of pharmaceutical patents, and not other technologies, arguably, constitutes a contravention of the non-discrimination provision in Article 27 of the TRIPS Agreement.

[37] 2017 Draft IP Policy p 24.

[38] 2017 Draft IP Policy p 24.

[39] 2017 Draft IP Policy p 5.

[40] Designs Act 195 of 1993.

[41] 2017 Draft IP Policy p 34.

[42] 2017 Draft IP Policy p 36.

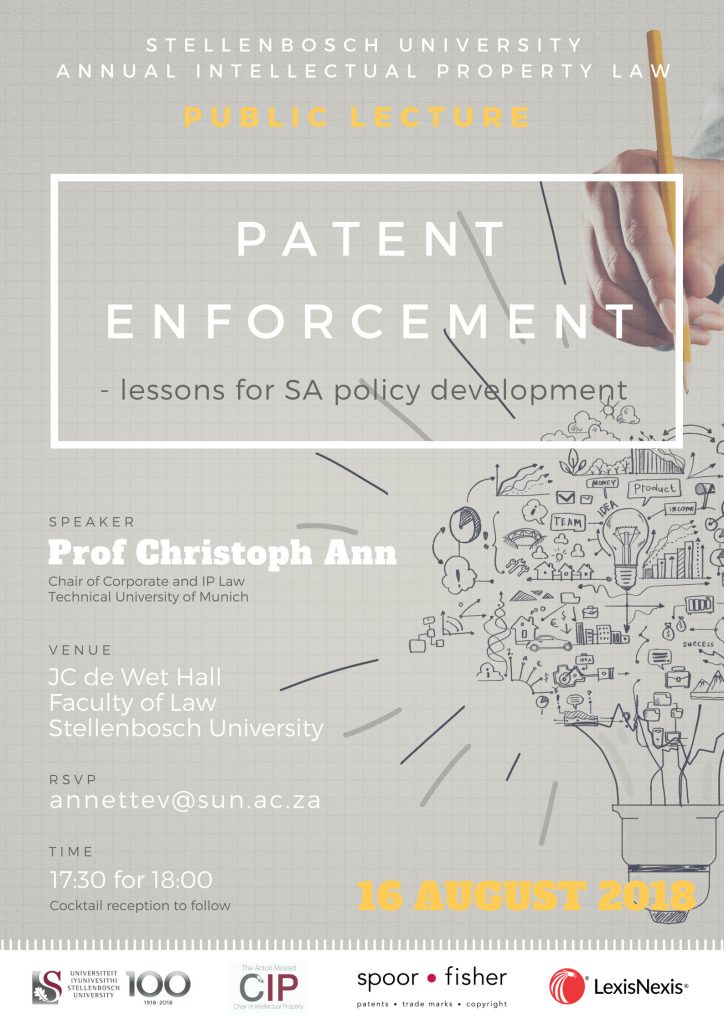

Professor Christoph Ann holds the chair of Corporate and IP Law (www.jura.wi.tum.de) at Technical University of Munich (TUM), School of Management. While TUM has been ranked one of Germany’s top three universities for quite some time, TUM School of Management was ranked Germany’s #1 Research Business School in recent years.

Professor Christoph Ann holds the chair of Corporate and IP Law (www.jura.wi.tum.de) at Technical University of Munich (TUM), School of Management. While TUM has been ranked one of Germany’s top three universities for quite some time, TUM School of Management was ranked Germany’s #1 Research Business School in recent years.