The Iziko South African Art Gallery is currently featuring an expedition entitled “A Centenary Celebration of the life and work of Barbara Tyrrell”. Barbara Tyrrell is a South African artist and author and the exhibition comprises a selection of over 150 of her highly decorative and accurate visual reproductions of Southern African tradition costumes and tribal dress, as well as items of adornment. The various subject matters comprise traditional South African art works and are themselves copyright artistic works.

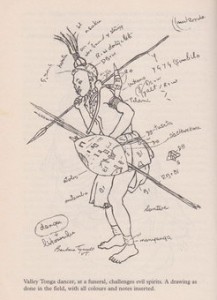

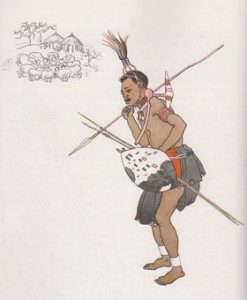

During the 1950’s and 1960’s Barbara Tyrrell undertook a journey through Southern Africa in search of the traditional dress of many different ethnic peoples inhabiting the region. She made countless sketches of traditional tribal attire, a large proportion of which were transformed into paintings. The exhibition of her works constitutes a marvellous vivid and colourful collection and record of a very wide variety of traditional attire and items of adornment. It provides a remarkable catalogue of traditional South African art works associated with clothing and attire and is probably a unique record of truly traditional African artworks. Her works currently form part of the Campbell Collections housed at the University of Kwa-Zulu Natal.

In the course of compiling her collection of works and when Barbara Tyrrell visited villages and other tribal habitats she communed with the tribes and peoples and made her drawings and paintings with their concurrence and blessing. The works were made in a relaxed and comfortable environment with the minimum of formality and bureaucracy. She simply travelled through the countryside and drew and painted what she saw while visiting local peoples and villages. In this way a valuable cultural and historic collection was assembled. She is now one hundred years old and her works will thus continue to enjoy copyright for at least the next fifty years.

Let us now fast-forward some sixty or so years to the year 2014. By this time, the Intellectual Property Laws Amendment Act, 2011, which was passed by Parliament in 2011, will presumably have come into operation. President Jacob Zuma will hopefully have broken away from his nuptial activities for long enough to signify his presidential assent to this Act and other acts passed by Parliament during 1911.

The Copyright Act and various other intellectual property statutes have by now been amended so as to provide IP protection for so called “traditional knowledge”. In a copyright context this term really means expressions of folklore and, more particularly, for present purposes, traditional art works. Traditional art works now enjoy retrospective copyright going back to the days of yore, extending forward in perpetuity, and they have been transformed from cultural treasures to items of commercial property capable of generating revenue. All the facilities and bodies created by the amending Act have been put in place and are operational. So, we have an august body known as the Council of Traditional Knowledge, a Traditional Knowledge Trust operating a trust fund, and a National Database, intended to provide a record of all and every work of traditional knowledge, regulating the traditional copyright industry. These entities are staffed by large numbers of people (cadres to whom some or other political debt is owed?) and a thriving bureaucratic apparatus is in full sway. The national objective of providing employment has been served (but is anything actually being produced or created ? – no mind)

Each and every work of traditional knowledge, and in particular traditional art, is the subject of copyright, no matter when (perhaps hundreds of years ago) and how, or by whom, it was made. Who or what is a “community,” owning copyright, remains uncertain. Is it an extended family, the members of a village, a clan, a tribe or a nation, such as the Zulus, as a whole? The owner of the copyright (the nebulous “community”) is entitled to require the payment of royalties in respect of the right to make reproductions and otherwise disseminate copies, of an artwork. Licensing of copyright is the order of the day, and indeed, a licence agreement with the text and conditions approved in advance by the Council of Traditional Knowledge is required to be signed. The royalties payable for using the work could be paid to the National Trust whereafter, after deduction of administration costs, some of it may, but not will not necessarily, flow back to the “community” from which it originates. Dissemination of longstanding traditional culture is now a business aimed at making a profit. The destination of the bulk of the royalties collected is, however, obscure.

Armed with her prior approved draft written licence agreement, a latter-day Barbara Tyrrell comes to a village in East-Griqualand and wishes to observe an initiation ceremony so that she might draw pictures and make paintings of what she sees, and in particular the costumes to be worn by the various participants. She will no doubt be charged an admission fee to witness the ceremony because “traditional performances” are now protected by the Performers Protection Act and consent (to which a price can be attached) is necessary to make any form of recording of what transpires. If the relevant community has appointed a collecting society to look after its money collections, as it is entitled to do, she may be able to negotiate with the collecting society. Otherwise, she must negotiate with the “community”, whoever that may be. Assuming the negotiations are successful and the licence agreement is signed, she will be entitled to make one or more drawings or paintings of what she sees, subject, of course, to the conditions of the licence. A licence is required in respect of each and every work reproduced. One hopes that she has a clear idea of what she ultimately intends to do with the pictures because that may influence the terms, and the cost, of the licence.

One of the major difficulties she faces is that she must determine which “community” is the copyright owner. This is the community in which the work originated or first saw the light of day. Since any community (whatever that may be) can subjectively determine whether a work is a traditional work of theirs, it may be that more than one community claims copyright in a particular work that she wishes to reproduce. In fact, there may be a dispute between several communities as to which community is the actual originator of the work. This enquiry may go back several hundred years. Was the work originally traditional to a Zulu community, or a Xhosa community? Did it originate with a Zulu community and was it then adapted by a Xhosa community, in which case each of the communities will own the copyright in separate aspects of the traditional work? If she is wise she will require the community with whom she ultimately enters into a licence agreement to furnish her with a warranty that it controls the copyright in the desired work and a corresponding indemnity against adverse claims being made against her. Indeed, she would be well advised to travel with her intellectual property attorney so that she can be advised as to the intricacies of copyright law as applicable to a myriad of traditional works. Otherwise she faces severe risks that, despite paying licence fees, she could end up infringing someone’s copyright and be liable for payment of damages.

One can understand that if the latter-day Barbara Tyrrell travels to a variety of communities in different parts of the country, and paints in excess of 150 different works (like her predecessor did), she will have her time cut out to sort out all the complex legal and commercial issues. A considerable amount of advance planning would have to go into the expedition so that she could ensure that she is armed with the prior approved written licence agreements when she arrives on the scene. No random wandering through the countryside this time round. It has all become terribly complicated.

One cannot help but ask the question whether a latter-day Barbara Tyrrell, or anyone in his or her right mind, would ever in a million years contemplate embarking on such a project at all. Given the hassles connected with it, there is scant prospect of this happening. However, it would be a great pity if she decides against it because this means that no record of the costumes used across the length and breadth of the nation would be created. Consider the sad cultural loss that would have occurred had Barbara Tyrrell been deterred from undertaking her project all those years ago.

There may, however, be some consolation to the latter-day Barbara Tyrrell. A silver lining to a very dark cloud, perhaps! Her logistical problems may conceivably be alleviated by the fact that, since a State-run database of traditional works has been created, each and every community will have gone to the trouble and expense of registering each one of their traditional art works in the database. Ascertaining comprehensive details of works and their ownership may be available at the simple press of a button. After all, an expensive and comprehensive database has been put in place at State expense and it would be a pity if it is not property utilised to the benefit and for the convenience of the Barbara Tyrrells of this world. The legislation is, after all, very far sighted and imaginative. Why would rural traditional communities not take the elementary step of registering their comprehensive portfolio of traditional works in the database in Pretoria? Surely this would be the passport to instant commercial success in commercially exploiting all their longstanding traditional works. It may well be worth the vast cost of the registration process.

The difference in the operating circumstances between, on the one hand, the Barbara Tyrrell of the 1950’s and 1960’s, and, on the other hand, the latter-day Barbara Tyrrell, must be attributed to the progress that has taken place in enabling traditional communities to commercially exploit their ancient traditional treasures. There is money to be made from the commercial exploitation of past traditional works and the communities have now been empowered to grasp some of that money. The treasure houses of the past have been unlocked. There is now no need to create any new works for the future. Why work at creating something new – expend trouble and talent – when there is plenty of money to be made from what has already been done in the past. One can simply sit back and reap the fruits the endeavours of the forefathers. Who needs the incentive of ongoing creative activity and achievement for future reward and the enrichment of art and culture? The pot of gold in the rainbow nation lies in the distant past, at the beginning of the rainbow. Cast your gaze backward, not forward!

It is a supreme irony that, assuming the latter day Barbara Tyrrell paints pictures featuring traditional art works, the copyright in her works will expire fifty years after her death and then fall into the public domain, as is the wont of intellectual property. It will be free for use, and to be built on for the future, by all. The copyright in those traditional art works depicted in her paintings will, however, on the other hand endure and be able to generate income for the fortunate communities forever. This is the bounty bestowed on the products of the ancestors by the amended copyright law. Perhaps there is after all also a pot of gold at the end of the rainbow, if it is ever reached! But, and herein lies the rub, is it possible that sane people will decide to give traditional works a very wide birth in conducting their commercial activities and that in reality there is no pot of gold at all?

Prof Owen Dean

7 April 2012