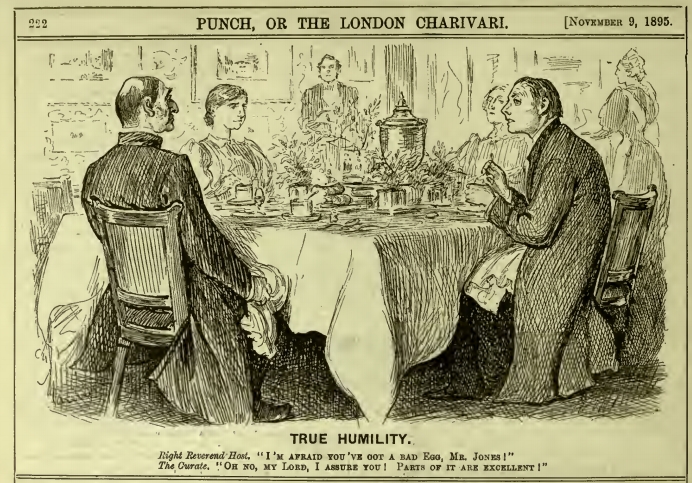

The figure of speech used in describing something as a “curate’s egg” derives from a cartoon by G du Maurier published in the British humorous magazine Punch in November 1895. It depicts a meek curate, faced with a bad egg at the Bishop’s breakfast table, commenting that it is partly good. In other words it is something that is thoroughly bad but is discreetly said to be partly good.[1]

“The term relies on an objective analysis and intuitive understanding of the depicted scenario: a self-contained egg cannot be both partially spoiled and partially unspoiled. To pretend to find elements of freshness in a bad egg is thus a desperate attempt to find good in something that is irredeemably bad.”[2] [Click here for more information].

The Copyright Amendment Bill published by the Department of Trade and Industry in GG no. 39028 of 27 July 2015 is an archetypal curate’s egg. I will commence by making a desperate attempt to find some good in it, which indeed there actually is.

The Bill addresses certain issues that have been crying out to be dealt with for decades. It thus in principle makes laudable strides to modernise the Copyright Act, 1978 which has become badly out of date, having received scant substantive attention from the legislature for some two decades while the world, particularly in the technological field and more particularly the internet, has been moving forward at a terrifying pace. The Act has simply become outdated and is in grave need of modernising and being brought into line with contemporary reality. The worthy issues that it confronts and seeks to regulate include the control of collecting societies; broadening the scope of exemptions from copyright infringement by providing for instances of so-called “fair use” of copyright works, particularly in the field of education; creating facilities for making works available to persons with disability on equitable terms; making provision for access to and use of so-called “orphan works” (i.e. works in respect of which the ownership of copyright is unknown); providing for sanctions for abuse of digital rights management measures built into copies of works. In so doing it is purporting to give effect the report of the Copyright Review Commission dating from 2011. So far so good.

On a perhaps less favourable level, the Bill introduces the European “droit du suite” in terms of which an artist can claim to receive a portion of the resale price of his artwork when onward sales of it are made; it provides for performers to have the moral rights of being acknowledged when their performances are publicly commercially exploited and of objecting to distortions of their performances (which provisions belong in the Performers Protection Act, which is their home); there is a provision prohibiting the purported granting of licences in situations where no right capable of being licensed exists.

But that is where the illusion of goodness in the Bill ends. I say this because, although the sentiments of the draftsman are commendable, the execution is abysmal. With more than 40 years of specialising in the practice of copyright law and having done a doctorate and written a text book on the subject, which has been cited with approval by the court on many occasions, as well as having pursued an academic career in the field, I can safely say that I know my way about the copyright world. I regret to say that I have not come across a piece of intellectual property writing that is as badly formulated and presented, and that exhibits such a lack of understanding of the basic principles of the subject as is evident in this Bill. The draftsmanship and usage of grammar and language in writing it are appalling. On a substantive level, it is as though the author of the Bill did not take the trouble to read, let alone understand, the Act that he is purporting to amend. It contains terminology which is foreign to the Act and rides roughshod over the basic principles of copyright law. The Bill is riddled with contradictions and anomalies; it is frequently non-sensical or downright incomprehensible even to someone who can claim expert knowledge of the subject matter. If, as a Professor of Intellectual Property Law, this Bill was served up to me as an answer to an examination question or as a dissertation, I would award it an assessment or mark of less than 20%. I would suggest to the student that he rather goes and pursues some other avenue of study as he clearly has no aptitude for copyright law.

I have described the good part of the egg as best as I can find it. Let me now go on to the bad part. In the interests of keeping the length of this epistle within reasonable bounds, I will deal with examples and will not seek to catalogue all the defects. This latter task will be undertaken in the comprehensive commentary which the Anton Mostert Chair of Intellectual Property Law will submit to the DTI within the thirty days from publication of the Bill (by 26 August) which has been laid down for the submission of comments, a ridiculously short period given the amount of work involved in formulating rational and constructive comment on this lengthy piece of balderdash (some 50 pages of taxing and perplexing text).

At the outset it must be borne in mind that our copyright law is determined to a significant extent by the Berne Convention and the TRIPS Agreement by which we are bound and with which our copyright legislation must comply. One of the fundamental principles of these treaties is “national treatment” in terms of which our law must give the same protection and benefits to foreign works as it gives to its domestic works. We cannot give preferential treatment to domestic works over foreign works. Furthermore, the fundamental approach of both our and foreign copyright law is to have a restricted selection of works eligible for copyright that are mutually exclusive. There is no overlap between the various categories of works.

With scant regard to the latter principle, the Bill appears to have created two new categories of copyright work, namely “craft works” and “phonograms”. These categories of works will have to co-exist with the existing categories of “works of craftsmanship” and “sound recordings” from which they are virtually indistinguishable. There is no conceivable justification or logic in creating these two new categories of works eligible for copyright when the Act already has two identical categories which have been part of our law for the best part of a century and which operate perfectly well. What the Bill does is to provide for the content of the copyright in these two new categories without laying the ground work for their coming into existence as occurs with all the existing categories. There is thus no way of knowing how and whether works of this nature qualify for copyright. The category “phonogram” is foreshadowed in the Bill by purporting to amend a definition that does not occur in the Copyright Act but is to be found in the Performers Protection Act (which is thankfully not addressed in the Bill).

The Bill requires the “broadcasting industry” to meet certain local content requirements in their broadcasts and even to oblige the institution regulating broadcasting to use measures to ensure compliance with the local content requirements. How can the broadcasting industry compel ICASA to do anything? This is putting the cart before the horse. What all this has to do with copyright is beyond my comprehension and provisions of this nature have no place in a Copyright Act which is concerned with the protection of original works, one category of which is broadcasts, the copyright in which is vested in the broadcaster who makes a broadcast – rights of a monopolistic nature in respect of its broadcasts are conferred on a broadcaster (that is the nature of copyright). In any event giving preference to local content (literary and musical works, sound recordings and cinematograph films that are locally made) in the Copyright Act brings the Act into conflict with the national treatment principle discussed above and is thus in conflict with our international obligations and probably unconstitutional.

Another breach of our international obligations is created in the provisions introducing the droit du suite principle in relation to artistic works. This right on the part of the “creator” of an artistic work (the Act does not use this term at all and one can but wonder who the “creator” of a work is as distinct from the “author”, the term used throughout the Act and internationally) is limited to an “artist” (someone different to the “creator” or the ”author”?) who is a citizen or resident of South Africa. This is a clear abrogation of the national treatment principle, with its attendant consequences. The provisions of the Bill dealing with this issue in general leave a lot to be desired and are unacceptable in their present form.

Section 9 of the Bill amends the existing section 9A of the Bill dealing with “needletime”. Sub-clause (b) to (d) of the amendment is completely duplicated by its sub-clauses (g) to (i), thus creating considerable confusion and evidencing shoddy draftmanship. Sub-clause (k) of the amendment has nothing whatsoever to do with needletime and probably belongs in section 23 of the Bill dealing with section 20 of the Act (moral rights). Aberrations such as this contribute to the unintelligible nature of the Bill.

The live performances by performers of works, i.e. singers, musicians, dancers and the like, are protected by the Performers Protection Act. Performers’ rights under this act are not copyright – they are rights somewhat akin to personality rights held by performers. A performer’s right is a cousin of copyright. These two types of rights often come together in a sound recording, which is a separate copyright work. A sound recording carries the performer’s rendition of a work (usually a literary and/or musical work). The Performers Protection Act creates economic rights in a specific performance, which rights vest in the performer. Protection of performance rights are dealt with internationally in a separate treaty (the Rome Convention) to the Berne Convention and our Performers Protection Act is closely based on the Rome Convention, as is performers protection legislation throughout the world. Performers rights and copyright are different animals. However, the author of the Bill has thought it good to reiterate some of the provisions of the Performers Protection Act dealing with the economic rights and their enforcement in the Bill. Apart from amounting to mixing apples and oranges, this will create enormous confusion and will undermine the integrity of both pieces of legislation. This is of course entirely unnecessary and undesirable and indeed makes no sense whatsoever.

The Copyright Act confers upon authors both economic and moral rights in their works. This is in accordance with the Berne Convention. Moral rights comprise the right to be identified as the author of a work and the right to object to alterations or mutilations of his work. In addition to conferring copyright economic rights on performers’ performances, the Bill also bestows moral rights on performers in respect of their performances. A moral right in a performance is a strange and remarkable concept and is not provided for in the Rome Convention. If it is to be provided at all it should be catered for in the Performers Protection Act and not in the Copyright Act.

The Bill introduces provisions allowing for permission to be obtained for the use of “orphan works”. Such works include works whose owner is deceased. The Copyright Act creates a right of property in a work and like all other forms of property this right of property can pass to an heir in terms of the Copyright Act and the law of succession. Accordingly, if a particular owner dies, his heir(s) acquire the ownership of the copyright. It is thus difficult to see why a work should become an orphan work when its owner dies. To make matters worse, the ownership of the copyright in an orphan work is vested in the State which can grant licences in respect of it and generate income for the State from its use. The copyright in an orphan work is perpetual, in complete abrogation of one of the basic principles of copyright law that a work should fall into the public domain after the effluxion on a specific time period. There is no reason why an orphan work should be in a preferential position as compared to a work that has a “parent”. Having provided that the copyright in an orphan work vests in the State, the Bill then goes on to provide in section 27 (introducing section 22A into the Act) that a licence can be granted in an orphan work and that royalty payments can be deposited into a particular account so as to enable the owner of the copyright or his heirs or executors to claim such royalty. This cannot be reconciled with ownership of the copyright in an orphan work (especially a work in respect of which the owner has died) vesting in the State. It makes no sense and is typical of the confusion and obfuscation that exists in the Bill.

Draconian criminal offences are created by the Bill for mild transgressions. For instance someone who contravenes the provisions relating to the payments due in terms of the droit du suite is guilty of a criminal offence! Likewise anyone who contravenes the provisions relating to orphan works. As a general rule infringements of intellectual property rights are civil law wrongs and only in exceptional cases do they constitute criminal offences. These rather innocuous transgressions do not warrant being criminal offences when more serious infractions are mere civil wrongs. Moreover, the newly created criminal offences are provided for in section 23 of the Act, which deals with civil copyright infringements, and not in section 27, which is devoted to criminal offences. This is but one instance of several where the existing format and system of the Act is disrupted and upset for no good reason. This is not at all conducive to coherent regulation of the law of copyright and interpretation of the Act.

There are a myriad of other problems attaching to the Bill that need to be addressed, but space does not allow for this here. In conclusion, the best approach would be for the DTI to go back to the drawing board and start all over again. Persons skilled in copyright law with drafting experience should be commissioned to draft the Bill to meet the Department’s requirements and thereafter it should be published again for public comment. Once it is in a presentable and lucid form, proper constructive debate and consultation can take place in regard to its content. No fruitful intercourse is possible with the Bill in its present incoherent state. The egg that has been dished up should be consigned to the trash can.

[1] http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/curate%27s%20egg

[2] http://encyclopedia.thefreedictionary.com/Curate%27s+egg

Paul says:

Thank you Prof. Dean for that lucid and entertaining article. This saves me the effort of reading draft legislation which is not advanced enough to comment on.

Unfortunately this is hardly the only instance of poor legislative drafting and the cybercrime bill and the amendment to the Electronic Communications and Transactions Act seem to suffer a similar fate.