The Copyright Amendment Draft Bill (GG No 39028, 27 July 2015) (‘the Bill’) is by all accounts a grave misfortune and a study in amateur law-making. Enough has been said on this point to make it clear that the DTI has tripped at the first hurdle and that a re-evaluation is the only hope of achieving a grade that would admit it to the Introduction to Copyright Law 101 examination.

However, it is noteworthy that the Bill contains a set of provisions that is worthy of (limited) praise and deserving of closer analysis. These are, among others, the proposed amendments to the Copyright Act (‘the Act’) that seek to incorporate anti-circumvention protection measures where a copyrighted work in digital format is protected by or controlled with the aid of digital rights management (DRM) tools or technological protection measures (TPM).

These provisions are long overdue and have been submitted to the DTI on numerous occasions in the past as proposed amendments to the Act that would update our desperately out-dated law and address the perennial piracy problem in a meaningful and coherent manner.

The application of intellectual property law in the digital environment is a technical, rapidly developing and highly skilled area of an already specialised field of law. The use of technology (such as TPM/DRM measures) in order to support copyright law adds a further layer of complication. It is therefore not surprising that the DTI has been slow to formulate South Africa’s legislative approach to copyright enforcement in relation to digital works.

One would therefore be pardoned for imagining that once the proposed amendments did eventually appear, they would be flawless and state of the art. However, one must be disappointed.

The Bill introduces several provisions that address instances where a copyright work in digital form, such as a cinematograph film, broadcast, computer program or sound recording, is protected by technological means.

Common examples of this practice are the digital copy restrictions applied to audio CDs or films on DVD/Blu-Ray Discs, access control measures applied to databases of literary works, device specific limitations applicable to sound recordings or eBooks, geographically specific encoding and authentication measures applied to video-on-demand and pay-TV services and serial keys applied to computer software.

These measures are largely developed and maintained by private stakeholders in the digital content and cybersecurity industries and have long been applied to enforce copyright law on the Internet and in relation to the digital versions of copyright works disseminated by electronic means. It has evolved to reach a degree of general standardisation for each type of work, with a few variations on the same theme. As a result, the use of DRM or TPM is a common phenomenon and a standard bearer of copyright law in the battle against piracy.

Therefore, the international IP community and its leading expert (the World Intellectual Property Organisation) saw fit to propose that all nations should adopt national legal measures that prevent or restrict the removal of or interference with any of these protection measures. Why? Because in most cases of piracy the technological barriers must first be removed or modified before the work can be reproduced and distributed. Therefore, if the law prevents the removal of such digital measures, it may limit the proliferation of copyright infringement of digital works.

The WIPO Copyright Treaty proposed that all member states should implement measures to address the circumvention of digital and technological measures applied to copyright works, and South Africa paid some service to this suggestion by enacting chapter 13, section 86 of the Electronic Communications and Transactions Act 25 of 2002 (ECT Act).

However, the ECT Act addressed circumvention along with other conduct such as hacking, denial of service attacks and malicious software in general as criminal conduct or cybercrime. The result was that circumvention for purposes of copyright infringement is currently a criminal offence and absolutely prevents fair dealing of copyright works in digital form.

As a result, further attention was needed to balance the public interest with the economic interests of the copyright owner. Enter the Bill.

The Bill provides that, inter alia, it would be an offence to make, import, sell, distribute, advertise, use or advise on the use of any “process, treatment, mechanism, technology, device, system or component that in the normal course of its operation is designed to prevent or restrict infringement of copyright work”.

In other words, if for example a person rents a movie on disc and copies that film onto his computer (a process that would require a series of steps to enable the computer to copy the content of the disc) he would be guilty of an offence in terms of the Bill (and the ECT Act). The same is true where a person modifies an eBook file to print it or makes a copy of a film downloaded from iTunes.

However, in this respect the Bill does nothing more than duplicate the effect of the ECT Act and continues to criminalise such conduct. At this point the diamond in the rough begins to lose its sparkle.

The mere fact that a work is recorded in digital form and protected against the threats of digital incursion, should not mean that the work is no longer available for lawful use in the same manner as its analogue version. A digital work is certainly deserving of greater legal protection against the greater threat of infringement posed by the Internet, but that does not mean that digital works are excluded from fair dealing.

In this respect the Bill should be welcomed. It has taken note of this fact and provides in section 28P that technological protection measures may be lawfully circumvented for purposes of fair dealing, but not for any of the purposes of fair use proposed by the Bill. In addition, it makes provision for individuals to seek help with circumventing such measures for a lawful purpose and establishes specific safeguards applicable to libraries.

Unfortunately, the Bill has not achieved the lofty goal it has set out to achieve. It falls desperately short of protecting the interests of the copyright owner of digital works and at the same time fails to provide sufficient freedom to the user of digital content.

Firstly, the anti-circumvention measures (with the exception of one) culminate in criminal liability in the same manner as the much criticised section 86 of the ECT Act. It therefore exposes each case of fair dealing with digital works to the threat of criminal sanction, as opposed to civil copyright infringement. It is difficult to understand why the DTI would amend the Copyright Act and fail to employ the existing three-layer approach to copyright infringement currently contained in the Act to enforce the anti-circumvention provisions. Nevertheless, the fact that anti-circumvention is criminalised outright means that the Bill had to introduce a convoluted set of provisions to address the level of guilty knowledge required on the part of the offender.

Secondly, the slapdash drafting of the Bill has caused a further undue limitation on the use of digital works. It provides that circumvention may be carried out for purposes of fair dealing (quotation, review, private use, research etc.) but it may not be carried out for purposes of fair use (such as cartoon, parody, pastiche, format shifting or educational activity as introduced by the Bill). This interpretation may be avoided by reading section 12A into the meaning of “a permitted act” in section 28P, but the question remains whether, if that was the DTI’s intention, why it was not expressly included by merely referring to section 12A. Furthermore, the Bill introduces a general fairness test in section 12A(5) against which all forms of fair use must be evaluated. The act of circumvention is therefore, on the above reading of the Bill, made subject to this test in section 28P(a). As a result, any lawful act of circumvention for fair dealing or fair use purposes may nevertheless amount to criminal conduct if it is, for example, found to be an excessive or disproportionate amount of the work that was reproduced. Since the act of circumvention must necessarily relate to the whole of the work, it will in most cases amount to an excessive use of the work.

All of the defects in the Bill raised above may be cured with a modicum of care in drafting and a less aggressive approach to anti-circumvention. However, this does not mean that any lesser degree of protection for digital works is proposed. On the contrary, the digital environment requires the most comprehensive legal approach possible to safeguard intellectual property. All that is proposed here is a splash of spit and polish to allow the diamond in the rough to reveal its true colours.

How the Bill should be adapted to give effect to this sincere desire for effective and fair protection, is explained by the Chair of Intellectual Property in its official comments, available here.

It should be noted that this is not the only shortcoming of the Bill in relation to technology and IP in the digital environment. For example, a further glaring problem is the omission of the new exclusive right of communication to the public in relation to broadcasts and computer programs. The opportunity to tackle piracy and geo-blocking circumvention to its fullest extent has been missed. This is a significant and worrying lapse in concentration that should be addressed without delay.

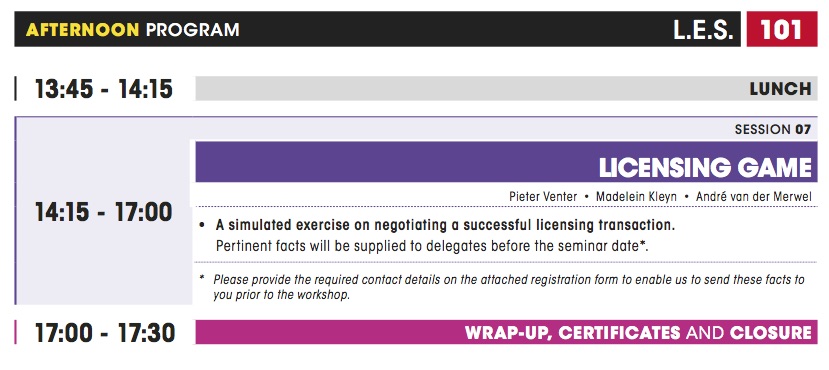

Cobus Jooste