Note: this post is part of a three part series on writing a literature review. For the first part see Slaying the (literature review) beast: Part 1.

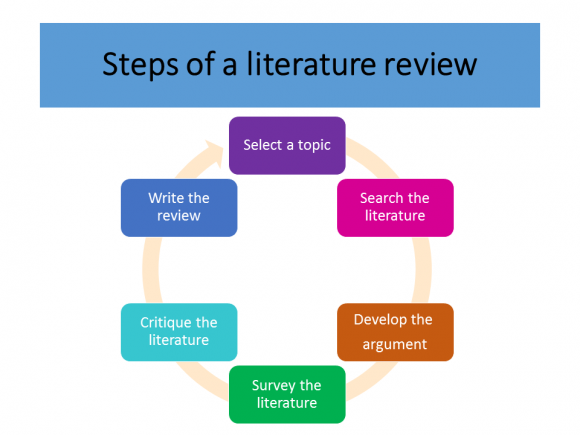

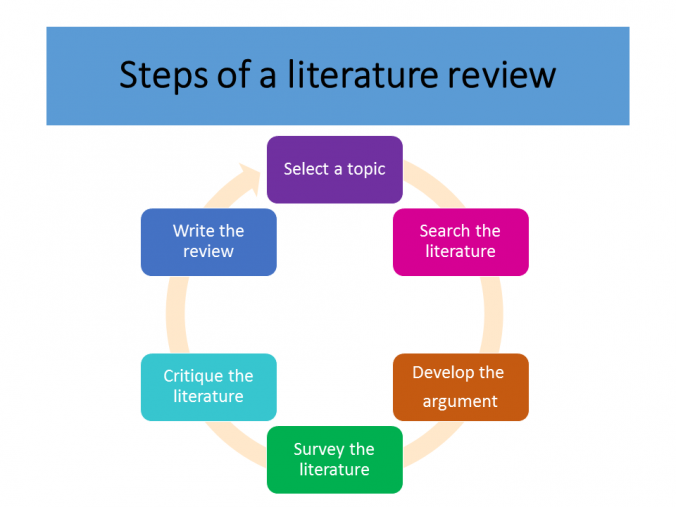

In this post, we will look at starting out on a literature review (selecting a topic, searching the literature and developing an argument). As a recap, here are the steps in a literature review:

Selecting your topic

Research stems from an unanswered question, and is usually fueled by a passion for answering that question. To create your topic, consult with your supervisor. As somebody who has knowledge in that field, they are able to guide you to where the gaps are for investigation.

Another way is to read – gather as many articles on your topic as possible (keeping it to the point) and read in order to develop it more.

Here are some more tips for creating a research question:

Searching the literature

This step is something that seems easy, but if you don’t have a good search strategy, it can quickly frustrate you. Let’s start with the obvious: Google does not have all the answers.

Although using a tool like Google Scholar can give you a good starting point, there are some dangers to only rely on it:

- Not all scholarly resources are contained in Google Scholar – publishers have to allow Google to access their resources, and some publishers have not done so. Therefore these valuable resources won’t even be searched (becoming invisible to Google).

- Google Scholar simply indexes, meaning it doesn’t do a value judgment. Therefore dodgy journals can make their way in. In this age, plenty of predatory journals exist – these are journals that will publish anything for a fee.

Your faculty librarian can really help you out here, by suggesting resources and strategies to use while searching. The library also offers a workshop called “Improving your literature search strategy.”

A search strategy sounds fancy but refers to what you type into the search box. For example, searching for articles on the economic history of Australia, you can simply type in:

economic history of australia

but databases are computers, and they don’t understand the meaning behind the words. So while the top results are relevant, after about the 4th or 5th article, it becomes completely irrelevant. A search strategy helps prevent that, by using punctuation and keywords to make the database understand exactly what you want.

So taking our same topic, we can apply things such as quotation marks (to indicate phrases – words next to each other):

“economic history” australia

Now your search will be more effective – saving you frustration and returning less irrelevant results.

The library also has a really great guide that goes into detail, giving valuable tips.

Skim reading

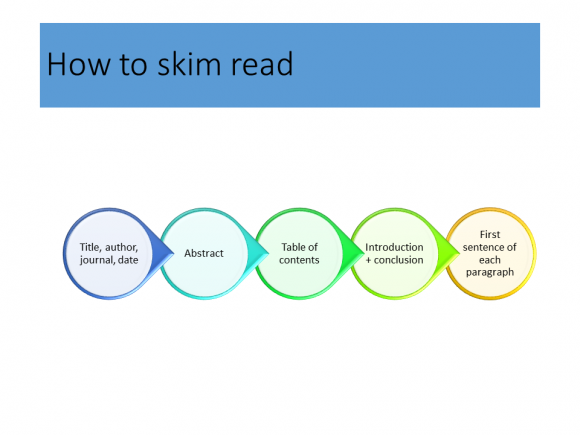

When searching literature a valuable technique is knowing how to skim read. Skim reading allows you to quickly grasp what the article is about, and its value.

NB reading an abstract alone is not sufficient – abstracts are made to ‘catch’ your eye and do not show the full value – or lack of value – the article has for your study.

Develop the argument

A literature review is a little more complex than simply a summary of your literature. Remember you need to add in your critical thinking skills, and relate the literature to your study – showcasing reasons why your study is needed.

In short, it is the reasoning for your study. You are saying “this is what has been done, this is what has been covered and this is why my study is needed / this gap is what my study will address“. It is meant to convince the reader of the importance of your study.

Developing this argument requires you to also write in a way that makes sense:

argument = Claim a (literature 1) + claim b (literature 2) = conclusion (your study reference)

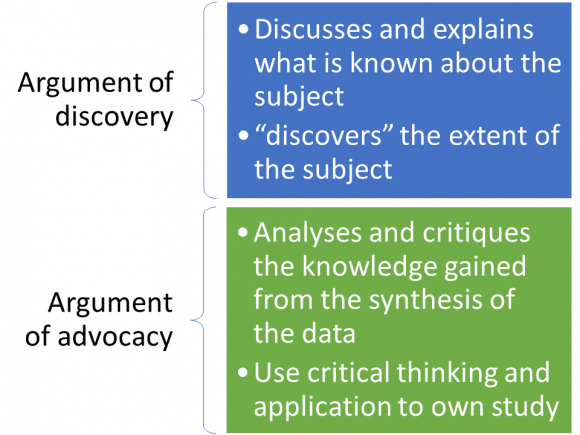

There are also two different types of arguments, and it is worth using both in your literature review:

Using these techniques allow you to say (blue for argument of discovery, green for argument of advocacy):

During 2006 and 2007 the University of Melbourne Library underwent major restructuring in terms of its vision for the library, the organisational structure and service model (Kealy, 2009: 573). This was in response to the library becoming more technologically advanced by offering information technology services and multimedia services within the context of new undergraduate degrees being offered at the university (Kealy, 2009: 573). The library was pro-active in adopting a new service model as it took cognisance of the fact that there would be a greater emphasis on supporting academics and their research; and ensuring that library staff were appropriately skilled to support these services into the future (Kealy, 2009: 573). This is a prime example of an organisation requiring to adapt and being flexible in a changing environment in order to remain relevant and competitive (Prahalad and Hamel, 1990: 1). Similarly, this study considers the current knowledge and skills humanities librarians possess as well as future knowledge and skills required in order to meet the challenges of a changing academic library environment.

– Excerpt from Johnson, G. 2016. A study of the knowledge and skills requirements for the humanities librarian in supporting postgraduate students. MPhil thesis. University of Cape Town: Cape Town.

You may be using these techniques without realising it, but if you are having issues with writing your literature review, it is useful to apply these techniques and it may just help things go more easily.

In our last post, we will discuss the final (more technically and tool-based) steps in the literature review, including how to manage your literature either manually or through using a reference manager.

Keep in mind that if you are feeling lost at any point with the structure and way of writing in your literature review, the Writing Lab has your back! Every Tuesday and Thursday at the Research Commons!

Thank you so much