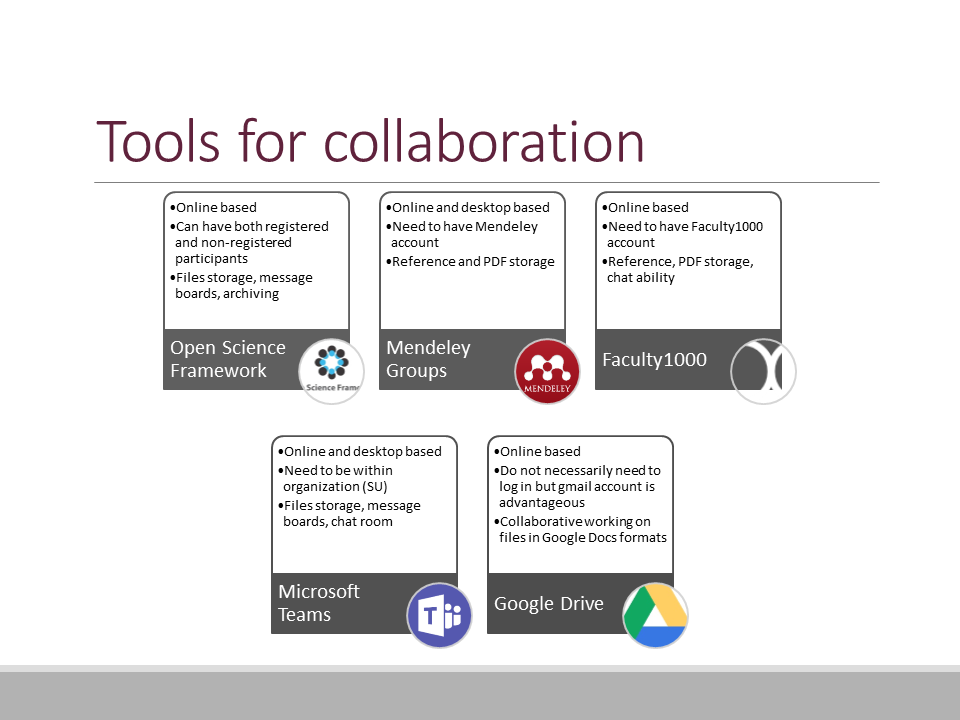

Wanting to take the pain out of collaboration? Here are some useful tools that will help you – with some basics about them:

Stellenbosch University Library and Information Service - News from research support services

Wanting to take the pain out of collaboration? Here are some useful tools that will help you – with some basics about them:

Often we get so busy that we don’t always have the energy or time to look up what’s happening in the world of research and news. To help you with that problem, here are some great online research based sites that you can sign up to their newsletters or just view their sites:

There are plenty more sites out there of course – if you are into literature you also have the New York Review of Books, the Paris Review, the Los Angeles Review of Books and the London Review of Books. Other thought provoking discussion and news sites include Aeon (tagline: a world of ideas) and Nautilus (tagline: Science Connected), while for news you have the option of a wide variety, with staples such as BBC, CNN, IOL, EWN, the Guardian and other ones perhaps new to you such as the Atlantic, The New Statesman (both UK and American), the New Republic.

My last honourary mention goes to Reddit – a forum for practically anything (tagline: the front page of the internet), letting you search for topics related to your interest. For example, the Reddit feed of Higher Education includes a number of articles from almost all the sites mentioned above, as it scrapes the internet daily to combine a news feed relating to higher education. It also includes user posts relating to higher education – such as advice for Masters students.

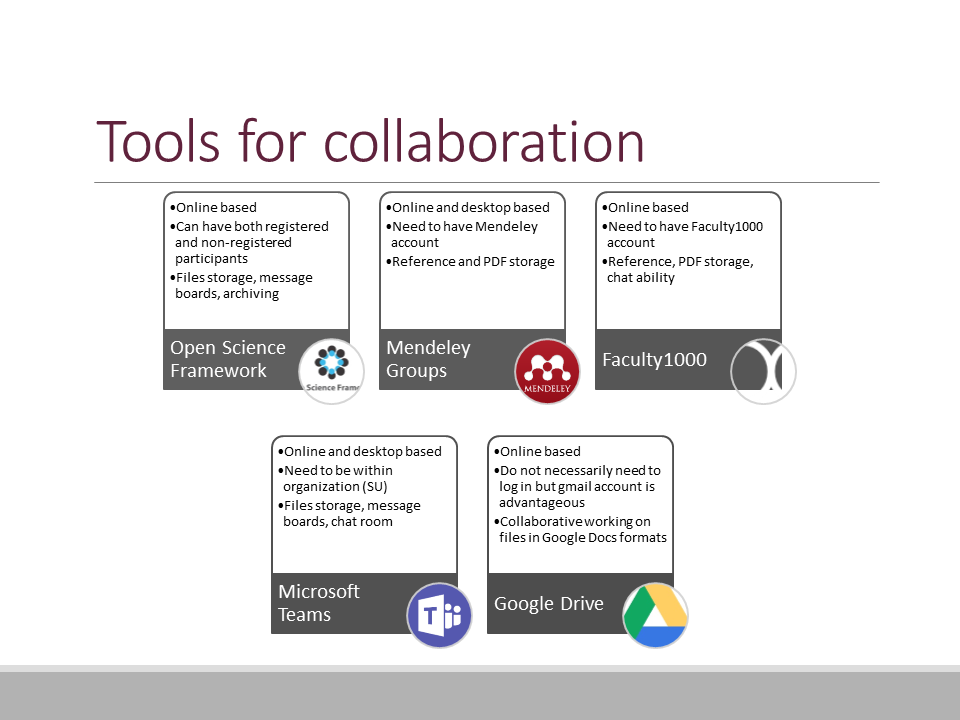

With all the above – we really have so much information available to keep us informed – the only thing left to do is to make sure that we don’t believe everything on the internet 🙂 Keep in mind to check for credibility (see below how), but you will see quickly the sites above pass the test.

Evaluating resources – the CRAAP test. From: https://libguides.spokanefalls.edu/c.php?g=288859&p=2711625

Note: this post is part of a three part series on writing a literature review. For the first two parts see Slaying the (literature review) beast: Part 1 and Slaying the (literature review) beast: Part 2.

So now we come to the last post on literature reviews, looking towards revealing some tips and tricks that will make the process much faster and easier.

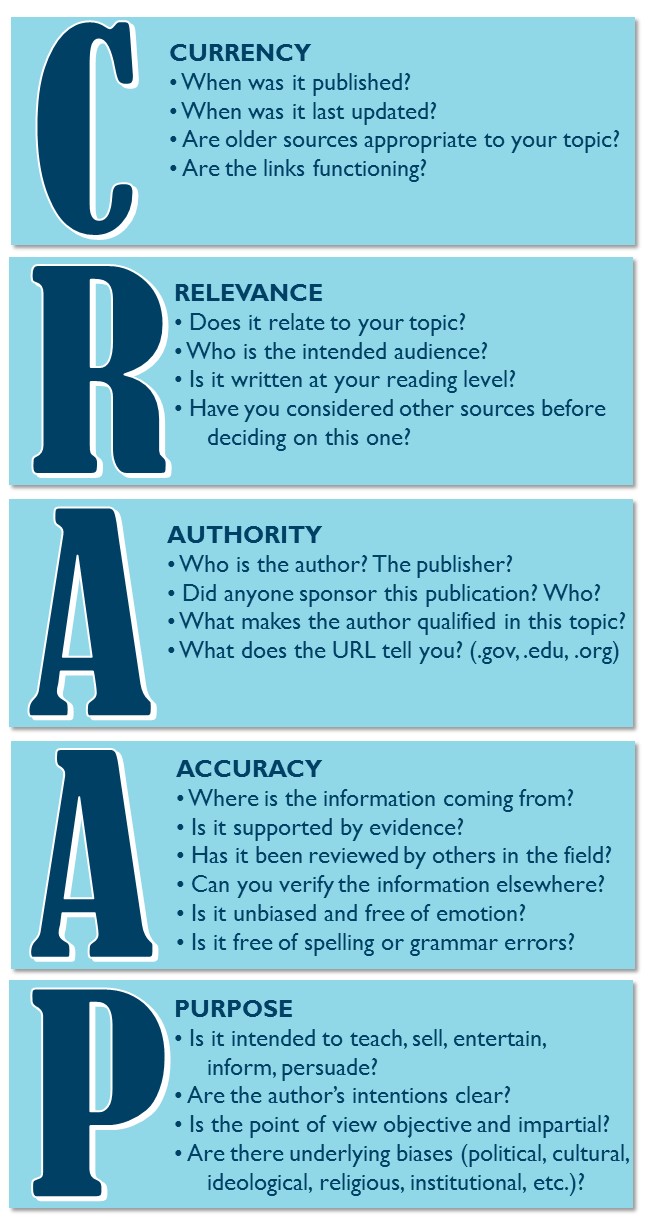

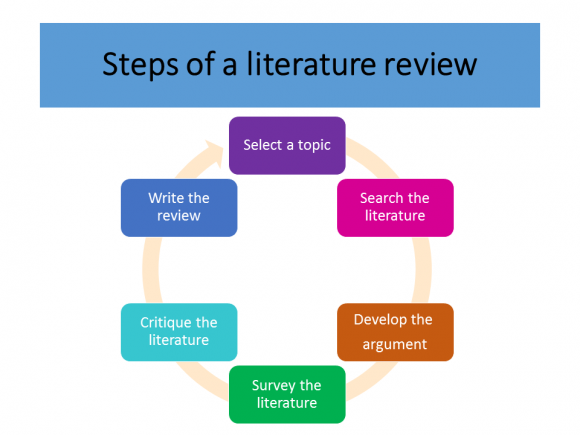

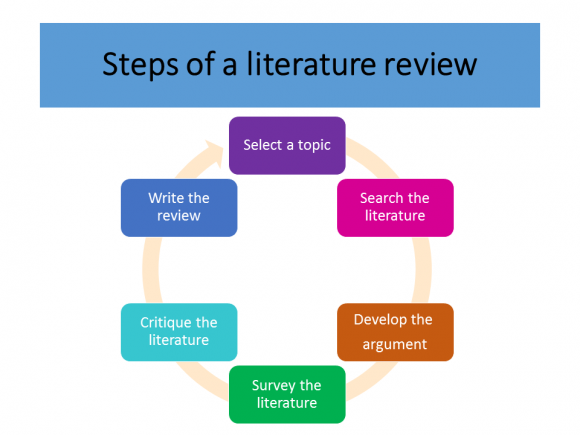

To start with, let’s recap the process:

In our last post, we covered the first three steps – selecting a topic, searching the literature and developing an argument.

In this post, we will cover managing your literature – helping you survey and critique it through making the management process less painful.

Surveying and Critiquing the literature

Using a reference manager to manage the literature

Keeping all your documents in one place sometimes becomes quite tricky, between working on different computers, even using different browsers changes where files are downloaded to. Using a reference manager – which is a computer program – allows you to keep the references of all your literature in one place and, depending on the program, allows you to attach the full text PDF to the reference.

There are a number of different reference managers: Mendeley, EndNote, Zotero, Refworks. The library runs workshops for introducing you to using Mendeley, including how to import references and manage them.

Using a reference manager has the added bonus of allowing automatic citation using the Mendeley Cite-O-Matic.

So how does it work? It is based on a desktop program that syncs back and forth to the cloud. A word plugin allows you to insert a formatted citation from your references while writing your document. For an overview of Mendeley, have a look at the video below:

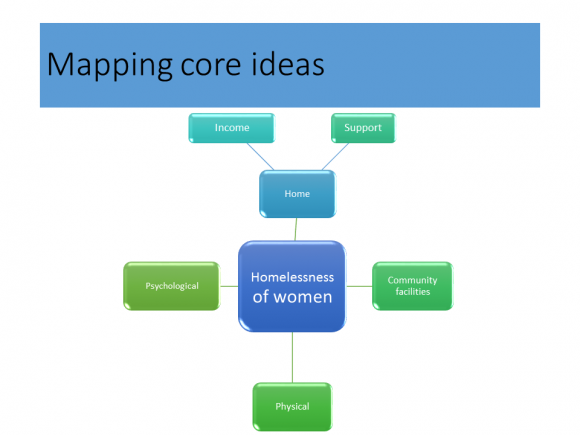

Mapping your core ideas

This may seem to be sending you back to your days of primary school, but a mind map of your concepts is genuinely a great way to plot out your literature review. This will let you plot out concepts related to your topic, and see quickly how the literature fits into it:

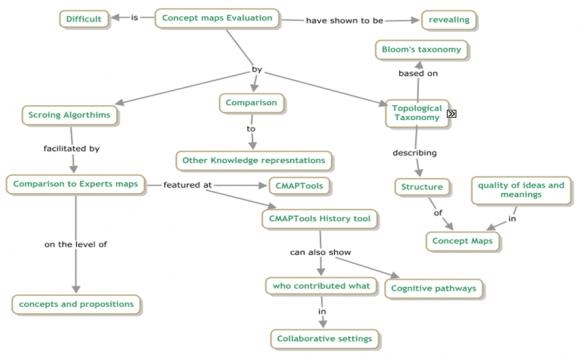

You can simply draw it out as well, but a fantastic tool to use is CMAP tool, which lets you easily create concepts and link them to each other. An example of a CMAP is below:

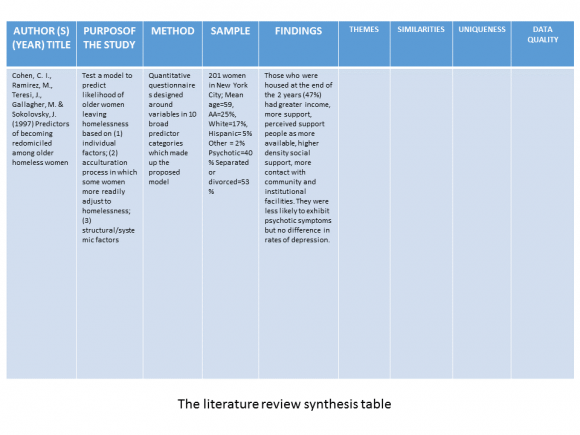

Literature Synthesis Table

A great handy tool is that of the literature synthesis table – this allows you to manage your literature by creating a table that summarises it. Initially this table can start to be filled out when gathering literature, and then further filled out when surveying and critiquing your literature.

An example is as follows:

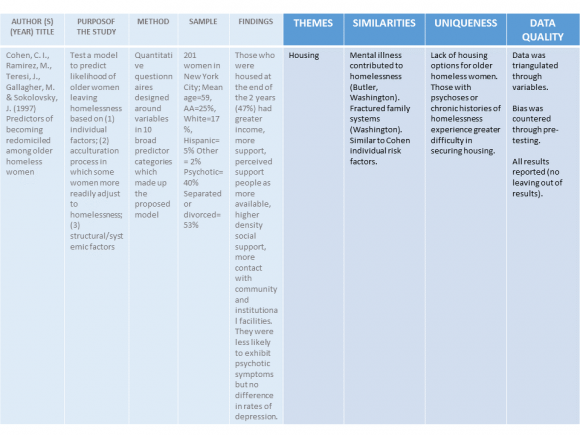

Literature gathering has started, and through skim reading (see Slaying the (literature review) beast: Part 2 for tips) certain information can be extracted already, such as the reference (author, year, title), the purpose of the study, methodology used, the sample and findings of the study:

Later, once you have collected all literature that you feel is relevant and you begin to read your articles thoroughly, you can then fill in the remaining columns – linking it to specific themes in your study, similar studies you have found, and the uniqueness of each article. The data quality links to the credibility of the study, so it is important to note, especially in this day of predatory journals where not all articles found are credible.

This table may seem like a lot of extra work, but it saves you a lot of time with regards to writing – you can immediately see which articles need to be grouped and why the different articles are important. A summary can easily be made in this way and transformed into a well-flowing, logical literature review.

That is to be said that this is simply a tool – it can only help as far as you let it – and it is there to be a guide. You can do the above without creating a specific table, through annotating PDFs, or through creating different folders with notes. It is all dependent on what works best for you.

Writing the review

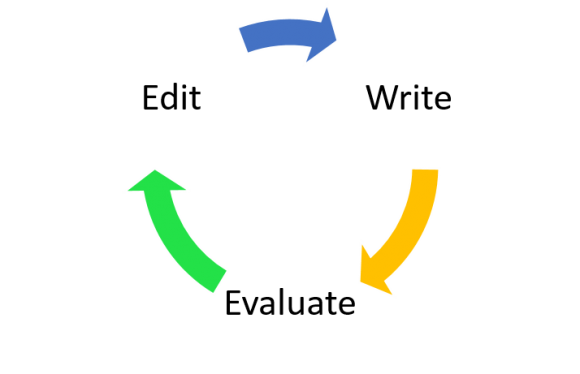

The last step is to start writing – with all the tools above, you should now have plenty to get started with. The writing process is a long one, because not only are you writing to understand your topic, you are writing to be understood as well. You will find yourself writing and rewriting as you evaluate what you have written:

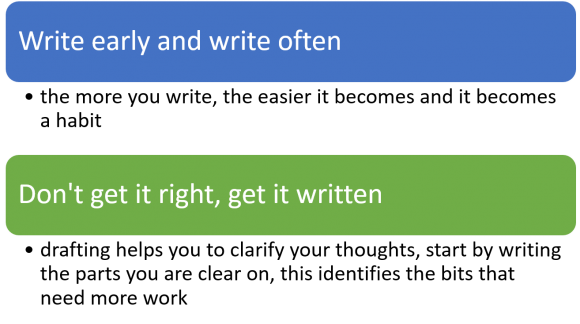

Some golden rules of writing are as follows:

Keep in mind the following:

Avoid the following:

Further writing tips are contained in the following:

There are many great resources out there, but another one I would take the time to mention is PhD Proofreaders . It is a great website that is FULL of tips and tricks for writing, including a PhD thesis-at-a-glance template and a checklist, helping you make sure you haven’t missed a thing.

There are plenty of other useful tools that you can have a look at to assist you during your thesis, and a great summary is contained in our Postgraduate and Researcher guide.

Remember that the library is there to help at any point! From our workshops to the writing lab availability in the Research Commons, to your subject librarian – we are all here to assist you to get through your studies with minimal frustrations 🙂

Note: this post is part of a three part series on writing a literature review. For the first part see Slaying the (literature review) beast: Part 1.

In this post, we will look at starting out on a literature review (selecting a topic, searching the literature and developing an argument). As a recap, here are the steps in a literature review:

Selecting your topic

Research stems from an unanswered question, and is usually fueled by a passion for answering that question. To create your topic, consult with your supervisor. As somebody who has knowledge in that field, they are able to guide you to where the gaps are for investigation.

Another way is to read – gather as many articles on your topic as possible (keeping it to the point) and read in order to develop it more.

Here are some more tips for creating a research question:

Searching the literature

This step is something that seems easy, but if you don’t have a good search strategy, it can quickly frustrate you. Let’s start with the obvious: Google does not have all the answers.

Although using a tool like Google Scholar can give you a good starting point, there are some dangers to only rely on it:

Your faculty librarian can really help you out here, by suggesting resources and strategies to use while searching. The library also offers a workshop called “Improving your literature search strategy.”

A search strategy sounds fancy but refers to what you type into the search box. For example, searching for articles on the economic history of Australia, you can simply type in:

economic history of australia

but databases are computers, and they don’t understand the meaning behind the words. So while the top results are relevant, after about the 4th or 5th article, it becomes completely irrelevant. A search strategy helps prevent that, by using punctuation and keywords to make the database understand exactly what you want.

So taking our same topic, we can apply things such as quotation marks (to indicate phrases – words next to each other):

“economic history” australia

Now your search will be more effective – saving you frustration and returning less irrelevant results.

The library also has a really great guide that goes into detail, giving valuable tips.

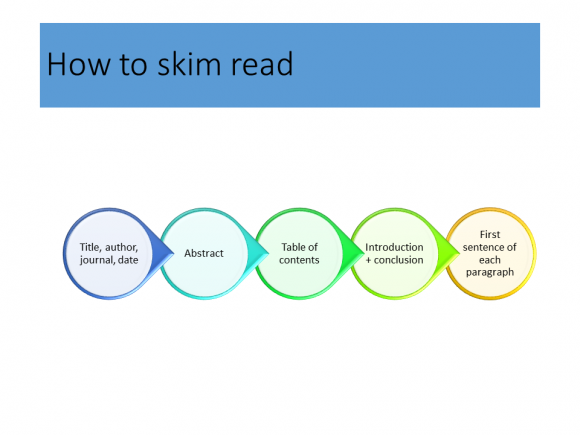

Skim reading

When searching literature a valuable technique is knowing how to skim read. Skim reading allows you to quickly grasp what the article is about, and its value.

NB reading an abstract alone is not sufficient – abstracts are made to ‘catch’ your eye and do not show the full value – or lack of value – the article has for your study.

Develop the argument

A literature review is a little more complex than simply a summary of your literature. Remember you need to add in your critical thinking skills, and relate the literature to your study – showcasing reasons why your study is needed.

In short, it is the reasoning for your study. You are saying “this is what has been done, this is what has been covered and this is why my study is needed / this gap is what my study will address“. It is meant to convince the reader of the importance of your study.

Developing this argument requires you to also write in a way that makes sense:

argument = Claim a (literature 1) + claim b (literature 2) = conclusion (your study reference)

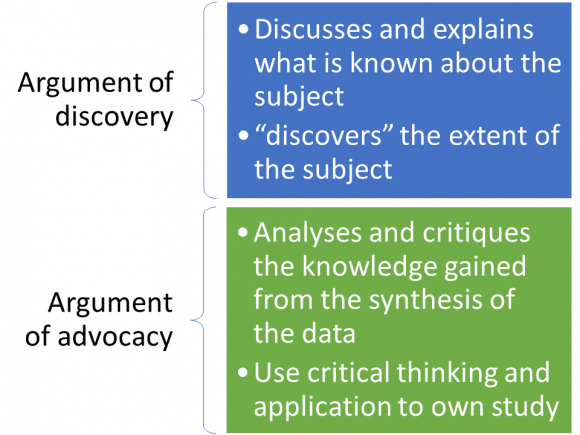

There are also two different types of arguments, and it is worth using both in your literature review:

Using these techniques allow you to say (blue for argument of discovery, green for argument of advocacy):

During 2006 and 2007 the University of Melbourne Library underwent major restructuring in terms of its vision for the library, the organisational structure and service model (Kealy, 2009: 573). This was in response to the library becoming more technologically advanced by offering information technology services and multimedia services within the context of new undergraduate degrees being offered at the university (Kealy, 2009: 573). The library was pro-active in adopting a new service model as it took cognisance of the fact that there would be a greater emphasis on supporting academics and their research; and ensuring that library staff were appropriately skilled to support these services into the future (Kealy, 2009: 573). This is a prime example of an organisation requiring to adapt and being flexible in a changing environment in order to remain relevant and competitive (Prahalad and Hamel, 1990: 1). Similarly, this study considers the current knowledge and skills humanities librarians possess as well as future knowledge and skills required in order to meet the challenges of a changing academic library environment.

– Excerpt from Johnson, G. 2016. A study of the knowledge and skills requirements for the humanities librarian in supporting postgraduate students. MPhil thesis. University of Cape Town: Cape Town.

You may be using these techniques without realising it, but if you are having issues with writing your literature review, it is useful to apply these techniques and it may just help things go more easily.

In our last post, we will discuss the final (more technically and tool-based) steps in the literature review, including how to manage your literature either manually or through using a reference manager.

Keep in mind that if you are feeling lost at any point with the structure and way of writing in your literature review, the Writing Lab has your back! Every Tuesday and Thursday at the Research Commons!

One of the first things that you encounter in your research journey is the Literature Review. It deserves capitals, because it is truly one of the beasts of academic writing. For this reason, I will speak to the literature review, revealing tips and tricks relating to it, in three different posts. This first post is a general overview of the literature review.

Perhaps the first thing to look at is why it is such a beast – the definition of a literature review is not simply that of a summary of literature, but it is much more complex:

So using this definition above, it can be seen that instead of just parroting the literature, an entire process takes place which includes critically thinking about the literature, applying it to your topic, evaluating the literature for both its strengths and its weakness, and attempting to guarantee that the literature you have found is a complete picture of all the literature written on that topic.

Breaking it further down, reading an article becomes a process that involves questions such as

It is no longer simply understanding the article that is needed, but also looking at it through a critical lense and seeing how the article is applicable to your study as well.

If this seems intimidating, then don’t worry – you are feeling the same as postgrads and researchers feel world wide. But we in the library specialise in working with information, and evaluating it – so we are here to help you!

Firstly – when writing the literature review, follow the following steps:

This post is the first part in a three part series on Literature Review. The next two posts will cover tips and tricks on creating a topic, searching the literature and organising your literature.

At some point in research the question “Which research method are you using?” comes up. For some disciplines (law as an example), the methods are almost pre-set, while other disciplines (such as the social sciences) have a much wider choice.

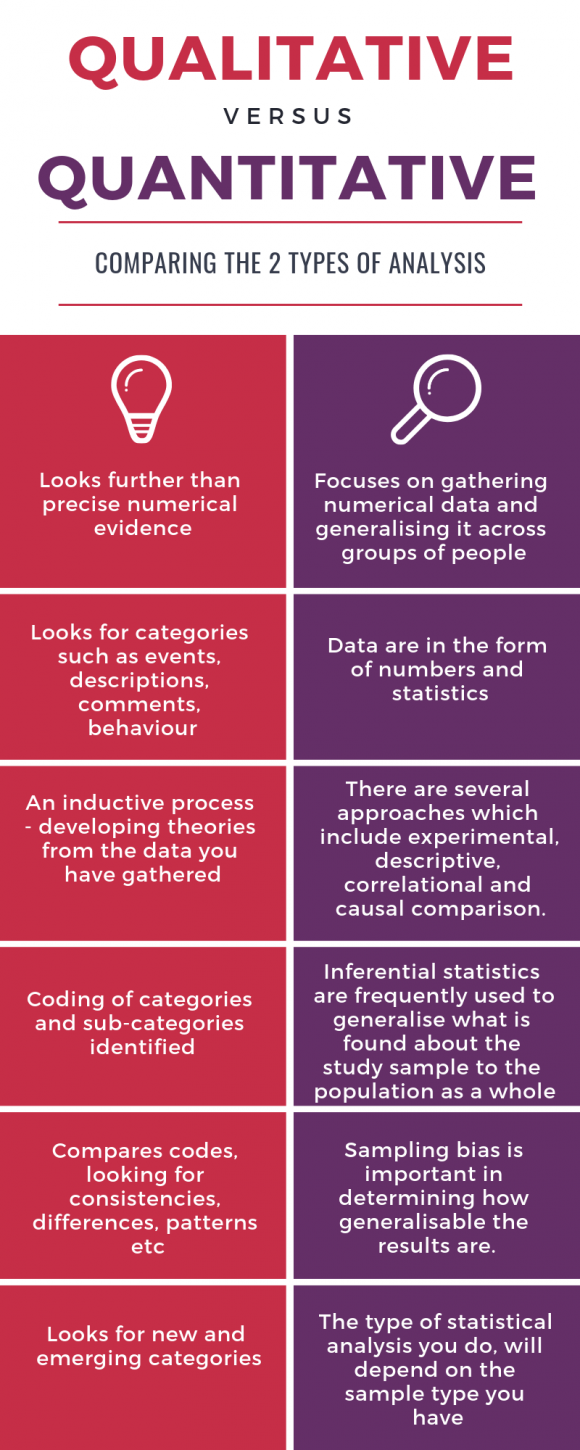

Research methods come down to two basic types: qualitative and quantitative. Quantitative (indicating that the data collected is in numerical form) and qualitative (indicating that the data collected is not in numerical form).

Often discipline determines which one:

Quantitative – the sciences, as most experimental data results in numerical data.

Qualitative – the humanities and social sciences (including law), as most data worked with is textual or informational, and not quantitative.

A useful summary of the differences between the two is here:

Over time, the social sciences and humanities have started to include quantitative methods as well, introducing a new category called mixed methods. This refers to a mixture of both qualitative and quantitative methods being used in the research.

Because of this, it often seems that research methodology books lean heavily towards the social sciences, as most authors that have written about research methods come from the social sciences.

However, these books speak to the concept of research methods and can be used across disciplines.

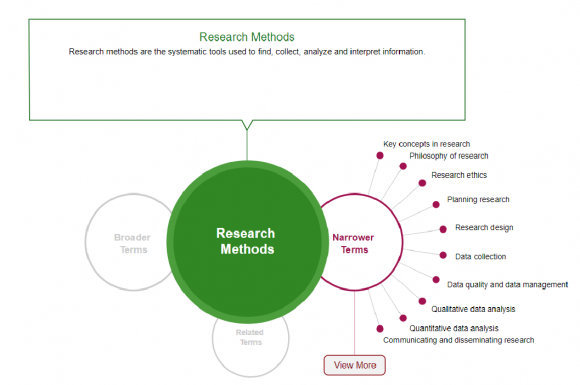

A great source for exploring research methodology is the database Sage Research Methods Online . This database has a great methods map, letting you delve deeper or wider into different methodologies and data collection techniques.

This is a great database loaded with information for those feeling slightly confused about research methods, or just needing some up to date sources to help.

There are also many helpful books in the library on research methodology – a useful shelf number is 300.72. In general though, if you are browsing in your subject area – look for books that are at the beginning of the shelves, and ending in .072 in number, and those will be related to research methodologies in your discipline.

It’s a new year and you are probably looking at trying to be more effective with your research. Perhaps you are just starting with your research, or perhaps you are wanting to optimise the way you work. Either way, we have the perfect tool for you!

Our full list of tools can be found on the Postgraduate and Researcher guide, but we have selected just a few here for you.

Productivity:

Freedom is an app and website blocker designed to improve focus and productivity. Use it to block apps on your phone, tablet or PC.

Planning:

Organise your thoughts, tasks and projects with Outliner. Create to do lists and track entire projects from anywhere.

Conceptualization:

The IHMC Cmap Tools software empowers users to construct, navigate, share and criticise knowledge models represented as concept maps.

Searching:

Fast, one link access to millions of research papers. Using the subscriptions of your university or institution, Kopernio provides access to full text pdf’s of articles directly from Google Scholar and other databases. Install the chrome plugin and tap into the convenience of Kopernio.

Reading:

A news aggregator application and RSS feed reader for various devices and web browsers. Stay up to date with the latest information in your field and keep track of your favourite publications all in one place.

Write up:

Grammarly is a free writing assistant that makes sure everything that you write is clear, effective and mistake free.

Noisli is a background noise and color generator for working and relaxing. Online soothing ambient sounds like White noise, Rain and Coffee Shop.

Referencing:

A free Reference Management and Academic Social Networking Tool that assists with managing your references, showcasing your work and connecting with other researchers worldwide.

Note taking:

Evernote is a cross-platform app designed for note taking, organizing,and archiving. Organise your work and take notes where ever you are.

Microsoft OneNote is a computer program for free-form information gathering and multi-user collaboration. It gathers users’ notes, drawings, screen clippings and audio commentaries. Part of the Office 365 student package.

Surveys:

The web-based e-Survey service (SUrveys) is available to support academic staff and postgraduate students using online surveys for their academic research.

Data Clean-up:

A free, open source, power tool for working with messy data.

Data Analysis:

R is a free software environment for statistical computing and graphics. It compiles and runs on a wide variety of UNIX platforms, Windows and MAC. Can be used with R-studio.

Visualisation:

Tableau Public is free software that can allow anyone to connect to a spreadsheet or file and create interactive data visualizations for the web.

Software use:

Oracle VM VirtualBox is a free and open-source hypervisor (virtual machine monitor) for x86 computers. If you need a specific environment for software use, Virtual Box can create it for you on your computer.

Collaboration:

A collaboration tool that bring teams together in a single workspace. Slack is where work flows. It’s where the people you need, the information you share, and the tools you use come together to get things done.

Manage:

Stellenbosch University Library & Information Service

For more information on Managing your Research Data, please see the Library’s Research Data Management page.

Store:

Get access to files anywhere through secure cloud storage and file backup for your photos, videos, files and more. Comes with 15GB of free space with your Google account.

A file hosting service from Miscrosoft. Students at SUN receive a 5TB OneDrive for use during their studies. See SUN’s IT page for more details.

Preserve:

Theses are deposited on SUNScholar once you complete your degree. SUNScholar can also be used to archive articles, conference papers and other records for long term preservation.

SHERPA RoMEO is an online resource that aggregates and analyses publisher open access policies from around the world and provides summaries of self-archiving permissions and conditions of rights given to authors on a journal-by-journal basis.

Presentations:

Web based presentation software. Prezi uses motion, zoom and spatial relationships to bring your ideas to life

Posters, Graphics & Infographics:

Canva makes design simple for everyone. Create designs for web or print, blog graphics, presentations, coves, flyers, posters and much more.

Sharing:

ResearchGate is a social networking site for scientists and researchers to share papers, ask and answer questions, and find collaborators.

A content sharing community for sharing of presentations and infographics.

Publish:

Think. Check. Submit. is a campaign to help researchers identify trusted journals for their research. It is a simple checklist that researchers can use to assess the credentials of a journal or publisher.

Where to Publish Library Guide

For more information about where to publish, have a look at the Library’s Where to Publish Guide.

Evaluate:

For more information on Research Evaluation and measurement, please see the Stellenbosch Library and Information Services’ Bibliometrics and Citation Analysis Library Guide.

© 2025 Library Research News

Theme by Anders Noren — Up ↑