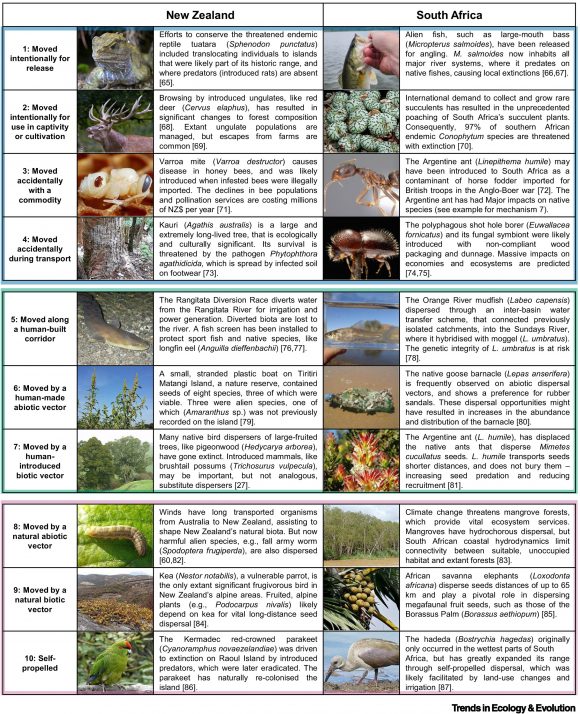

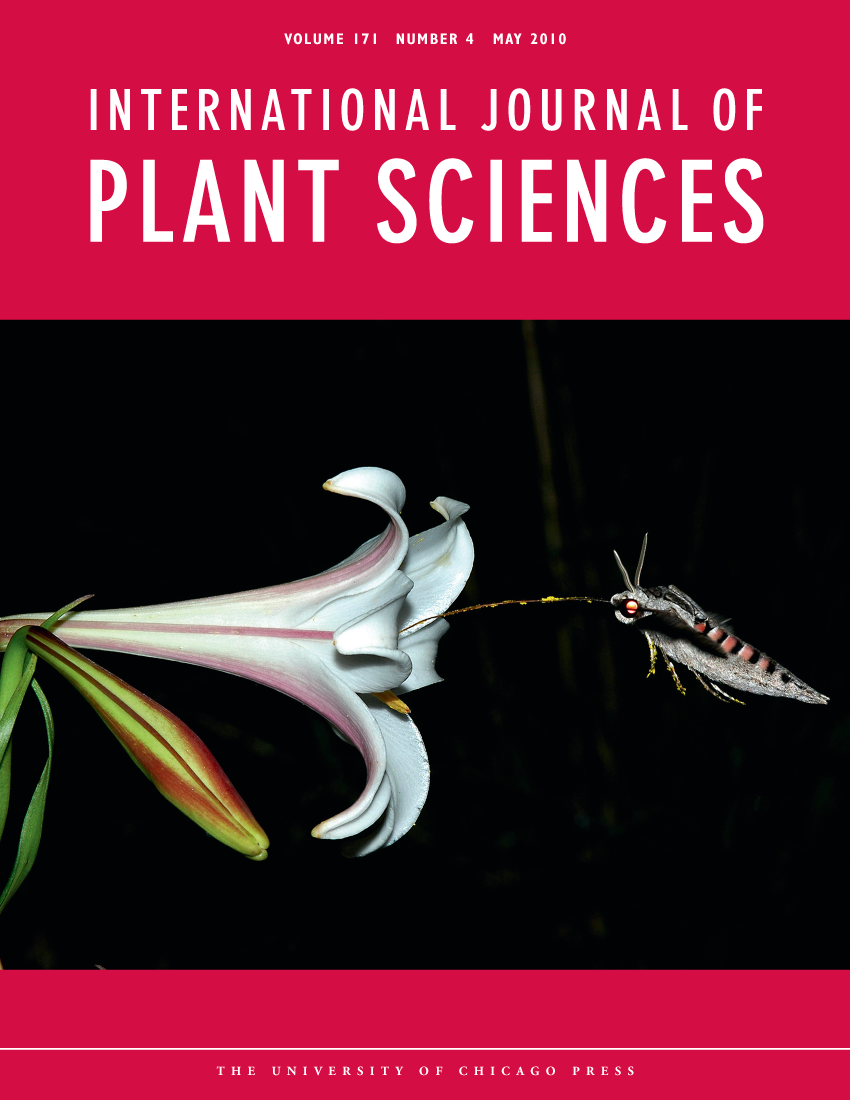

It’s an old idea that plants that are specialised for particular pollinators should become invasive less often than those which can be pollinated by a broad range of animal species. Most plant species will not encounter their original pollinators when introduced elsewhere so to reproduce in their novel range they will have to recruit novel pollinators. Although this is not a great challenge for the many species pollinated by a broad range of animal taxa in their native range, pollination specialists, it would seem, are unlikely to recruit novel pollinators and their invasion should be prevented by failure to reproduce. This has been shown to hold for species like figs, where pollinator distribution is quite restricted. C·I·B PhD student James Rodger, with supervisors and co-authors C·I·B core team member Steve Johnson and former C·I·B postdoc Mark van Kleunen, shed new light on this concept in a recent study that was published as the cover story in the May 2010 issue of The International Journal of Plant Sciences.

The authors investigated the pollination of the specialised plant Lilium formosanum (Formosa lily) in its invasive range in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. They found that reproduction of this species is partially dependent on pollinators although it is self-compatible and can set some seed by autonomous self-pollination. Flowers are pale coloured, scented at night and contain nectar at the base of a long floral tube, features typical of plants specialised for pollination by hawkmoths. The primary pollinator in Kwazulu-Natal is indeed a hawkmoth, the cosmopolitan Agrius convolvuli. Most intriguing is that A. convolvuli is indigenous across most of Africa and the warmer parts of Europe and Asia, including Taiwan. Agrius convolvuli therefore probably pollinates L. formosanum in its native range too. Upon introduction to South Africa, L. formosanum would then have found its original pollinator already present, so in this case specialised pollination would not have hindered invasion.

The prediction that specialised pollination systems should hinder plant invasions thus needs to be refined. Specialised pollination can be expected to impede invasion only when the pollinator species and functional groups onto which plants are specialised have narrow distributions. This improvement in understanding contributes to a longstanding and elusive goal of invasion biology- to be able to prevent invasions by predicting whether species will become invasive before they are introduced.

Contact the author: James Rodger

Read the paper

Read the paper