There are very, if any, ecosystems on Earth that are not substantially influenced by human activities. In most ecosystems, humans have changed many abiotic and biotic components, for example by changing disturbance or nutrient regimes and by adding or removing species. In many cases, the ecosystems that currently exist have no historical analogues; this greatly complicates the task of managers who seek to conserve local, regional and global biodiversity and to ensure the sustainable delivery of ecosystem services.

The concept of “novel ecosystems” was proposed by Richard Hobbs and co-authors in 2006 to provide a theoretical framework for understanding and managing those ecosystems with abiotic, biotic, and social components (and their interactions) that, by virtue of human influence, differ from those that prevailed historically, and which have a tendency to self-organize and manifest novel qualities without intensive human management.

The novel ecosystem concept has received much attention in the literature [the Hobbs et al. (2006) paper has been cited around 800 times at the end of 2014 according to Google Scholar]. Many authors have found the concept useful for devising sustainable management strategies for ecosystems affected by humans to the extent that restoration or rehabilitation to some historical state is either impossible/impractical or, for various reasons, undesirable. On the other hand, some authors have been highly critical of the “novel ecosystems” idea. One of the criticisms is that it is very difficult to define exactly what should and what should not be considered a “novel” ecosystem, since the thresholds that separate “historical” from “hybrid” and “novel” conditions are arbitrary and very difficult, if not impossible, to identify or recognize in practice. Some of the concerns of the detractors of the novel ecosystems concept are set out in these recent articles: “The road to confusion is paved with novel ecosystem labels” and “New normal’ approach to conservation comes under fire”.

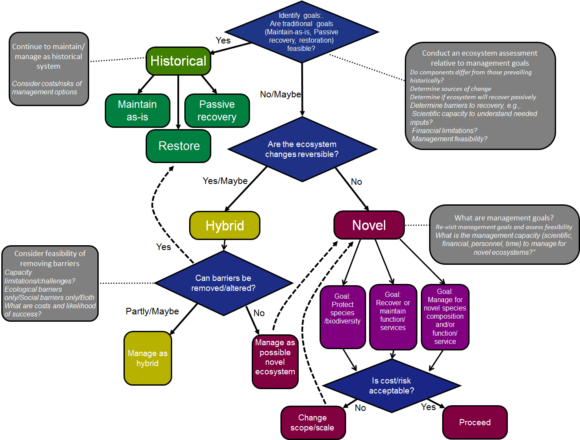

C·I·B Director Dave Richardson is a co-author of a recent paper entitled “Managing the whole landscape: historical, hybrid, and novel ecosystems”. This article sets out to review the applications of the novel ecosystems concept and to provide a “landscape management framework” to give guidance to managers who seek to ensure that limited resources are used most effectively. It provides further elucidation of the value of considering historical, hybrid and novel conditions and aims to counter some of criticisms levelled at the novel ecosystem concept.

“Much of the criticism of the construct of novel ecosystems (NEs) argues that by suggesting that such human modified systems can be effectively managed to deliver key ecosystem services, NE advocates are devaluing traditional conservation efforts that seek to prevent such degradation in the first place” says Richardson. “This is certainly not my view of the novel ecosystem concept!” he adds. “Huge areas are already substantially affected by humans and we desperately need objective ways of managing such land”. “In South Africa, for example, most of our riparian ecosystems are invaded by invasive alien trees and shrubs. Management interventions are underway to control and contain such invasions, to restore invaded ecosystems and to prevent further invasions, and such operations are essential. However, the scale of the problem is so huge that additional approaches are needed, for instance for riparian ecosystems in agricultural and urban settings. Biotic and abiotic conditions have been radically altered in these systems and restoration to some historical condition is unpractical. I have advocated managing such systems as novel ecosystems – I believe that it is entirely possible to identify sensible and defendable thresholds to guide management in a transparent and cost-effective way. Adopting such an approach should in no way undermine efforts to conserve ecosystems in a near-pristine condition is protected areas and other key sites”. For details of riparian ecosystems along the Eerste River which runs through Stellenbosch, where a novel ecosystems approach has been advocated, click here.

Read the paper