7 June 2021 | By Willem Nieman

African herbivores respond differently to recently burnt environments, and these differences can be heavily dependent on body size. This was the finding from a recent literature review conducted by PhD student Willem Nieman and Dr Alison Leslie (Department of Conservation Ecology and Entomology, Stellenbosch University), Prof. Brian van Wilgen (C∙I∙B Core Team Member) and Dr Frans Radloff (Department of Conservation and Marine Science, Cape Peninsula University of Technology) in which they describe the responses of medium- to large-sized African mammals to fire.

The review, published in the African Journal of Range and Forage Science, identified 64 studies that covered 51 mammal species from 34 locations across 10 countries.

Fire is a natural, frequent phenomenon in African ecosystems, and is often actively managed to achieve specific ecological or social goals. Most of Africa is also home to a diverse range of large mammal species that evolved in these fire-prone landscapes, but that now require active management due to declining population numbers in recent decades.

An understanding of how fire influences large mammals could be important for the management of both mammal populations and fire regimes, however, the relationship between fire and large mammals in Africa is not fully understood, and an updated review of available information was needed.

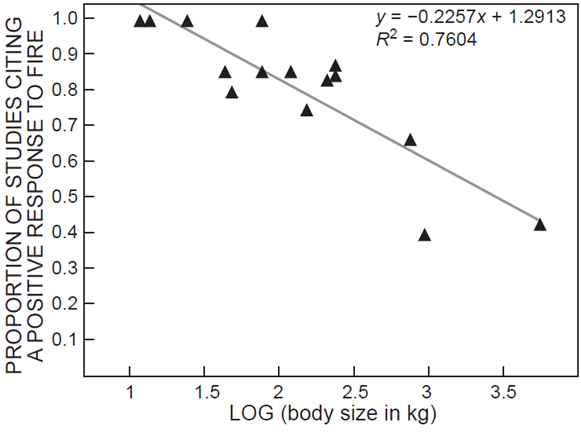

Differences in the responses of mammals to the aftermath of fire can be expected to depend on body size, because smaller-bodied species require more energy and nutrients relative to their body weight and should therefore be more attracted to burnt areas to benefit from the nutrient increases in post-fire regrowth. In contrast, larger-bodied species have greater gut capacity and retention time, and can therefore extract nutrients from the lower-quality forage in unburnt landscapes. Larger-bodied herbivores are also less vulnerable to predation, whereas smaller-bodied species may avoid unburnt areas that provide better cover for predators.

The review found a clear allometric relationship (the relationship of body size to shape, anatomy, physiology and finally behaviour of an organism), where smaller-bodied herbivores were more likely to respond positively to the presence of burnt environments than larger-bodied herbivores. This indicates that co-occurring mammalian herbivores have differing requirements for vegetation of different post-fire ages. For example, the tiny steenbok (Raphicerus campestris) would always choose a recently burnt environment, whereas the 6-ton African elephant (Loxodonta africana) always chooses unburnt habitats.

The authors therefore encouraged managers of protected areas to promote spatial heterogeneity through the use of fire to accommodate these differing needs.

“Manipulating specific elements of fire regimes to benefit herbivores is not always feasible,” says Willem Nieman, “but this work provides an important first step towards elucidating trends in large mammals’ responses to fire, and thus towards establishing guidelines to simultaneously optimise fire management and large mammal conservation.”

Read the full paper

Nieman, W.A., van Wilgen, B.W., Radloff, F.G.T., Leslie, A.J. 2021. A review of the responses of medium- to large-sized African mammals to fire. African Journal of Range and Forage Science 38(2): 1-15. DOI: 10.2989/10220119.2021.1918765.