Brian Van Wilgen, Stellenbosch University and Nicola van Wilgen-Bredenkamp, Stellenbosch University

The fires that started on 18 April 2021 on the slopes of Table Mountain in South Africa destroyed several buildings on the campus of the University of Cape Town. These included the Jagger Library, as well as the restaurant at Rhodes Memorial, the historic Mostert’s Mill, and several residential houses.

This was a tragic event that will affect many people for a long time.

Many questions have been raised as to why this happened, and whether anyone should carry the blame.

Based on our research into fynbos fire ecology and management over the past four decades, we believe that rather than attempting to apportion blame, South Africans should be examining the causes of destructive wildfires, and what can be done about them.

Wildfires are the inevitable consequence of three factors coming together at the same time: weather that is conducive to the establishment and spread of a fire; enough fuel of the right type and arrangement to carry the fire; and a source of ignition to start it.

Simple as this may seem, there are many misconceptions and poor understanding around each of these elements.

The weather

The Cape summer and autumn historically have suitable weather for fires to occur, so a fire at this time of the year isn’t unusual. However, global climate change is exacerbating the situation.

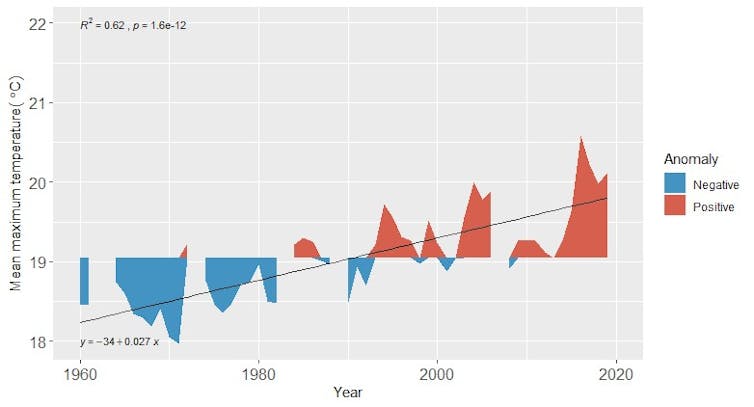

Data from the South African Weather Service Cape Point monitoring station show clearly that average temperatures have been rising steadily over the past six decades. As a result of this, the percentage of days with above average temperatures in April has doubled since 1960.

The steady increase in hot, dry weather will dry out the vegetation, making it more likely to catch fire, and for fire to spread. This phenomenon is not restricted to the Cape, and has been widely reported in other parts of the world.

Provided by lead author.

The fuel

The natural fynbos vegetation that historically clothed the slopes of Table Mountain is highly inflammable.

That situation has also been exacerbated by the introduction of alien trees, which increase the fuel available to burn, and that burn with a much higher intensity than the natural fynbos.

Read more:

Why the fire on Cape Town’s iconic Table Mountain was particularly devastating

For example, our work after the destructive fires in the South African coastal town of Knysna in 2017 showed that plantations of alien trees, and natural fynbos that had become invaded by these trees, burnt with much higher severity than uninvaded fynbos.

Alien trees don’t only increase the risk of uncontrollable fires, they also eliminate the natural biodiversity and reduce water runoff. This is particularly true if they become invasive, that is if they spread across the landscape without assistance, where they can form dense stands that crowd out the native fynbos and use more water than the vegetation that they replace.

In response to this, and in line with national legislation, South African National Parks has been clearing plantations of invasive pine trees from the Table Mountain National Park since the establishment of the park in 1998.

These operations have been conducted in the face of substantial opposition from the citizens of Cape Town, because the invasive trees are aesthetically pleasing and provide shade. Many people also believe (incorrectly) that they bring rain and provide the best cover to protect the soil.

Not all alien trees are invasive. It’s mainly invasive alien trees – those that are able to spread unaided across the landscape – that are targeted for control. The pine trees that have been removed from the Table Mountain National Park are invasive. The situation is further complicated because the trees in the line of most recent fires – mainly alien Mediterranean stone pines – are not invasive, so don’t have to be controlled in terms of South African law.

In addition, mature stone pines, including those at Rhodes Memorial, are protected by heritage legalisation and cannot be damaged or removed. These trees were planted over 200 years ago, and are valued icons of the city’s history. Whether or not, or to what degree, the stone pines contributed to the intensity and spread of the recent fires is not yet known.

What is known is that many buildings and historic infrastructure caught alight some distance from the fire front due to embers that were carried a long distance – an occurrence termed “spotting” by fire fighters.

Some (as yet unknown) plants, which include alien pines and palms, would have provided the fuel for those embers. Under these circumstances, even carefully maintained firebreaks would not have stopped this spotting.

Source of ignition

Research in other parts of the world has clearly demonstrated a strong link between human population density in an area, and the number of fires that occur.

Cape Town is now home to almost 5 million people, many of them poor and homeless. That fires will be started, either accidentally or deliberately, is therefore almost a given and very difficult to effectively prevent.

Urban densification, crime, and homelessness are broad social issues about which organisations like South African National Parks can do very little.

Going forward

Very little can be done locally about climate change – it is a global issue that must be addressed at a global scale.

The risks of human ignitions will remain a constant factor. That leaves two things that could be improved.

First, buildings should be fire-proofed as far as possible by using fire-resistant building materials and clearing gutters and other points where plant material accumulates. Secondly and most importantly, vegetation needs to be managed, especially tall alien trees that can significantly increase the risks of damaging fires.

Burning the fire-adapted and fire-dependent fynbos vegetation under milder weather conditions, and at appropriate intervals, to reduce fuel loads could also reduce the risk of runaway fires. This is currently impeded by very risk-averse wildfire legislation that needs to be carefully re-examined.

Dr Chad Cheney, a park planner at Table Mountain National Park, also contributed to this article.![]()

Brian Van Wilgen, Professor , Stellenbosch University and Nicola van Wilgen-Bredenkamp, Research associate, Stellenbosch University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.