13 June 2016 | By Mirijam Gaertner

A collaboration between C·I·B researchers and managers from the City of Cape Town’s (CoCTs) Green Jobs Unit resulted in the development of a framework specifically to help managers manage invasive species in cities.

The framework was published in the journal, Landscape and Urban Planning, by authors Mirijam Gaertner (C·I·B core team member), Brendon Larson (C·I·B research fellow), Ulrike Irlich (C·I·B research associate), Patricia Holmes (C·I·B research associate), Louise Stafford (Green Jobs Programme Manager), Brian van Wilgen (C·I·B core team member) and David Richardson (C·I·B core team member).

Cities are hotspots for invasions. High densities of people, transport linkages for example airports and harbours, and changed habitats facilitate the introduction and spread of invasive species. Managing invasive species in cities are a challenging matter as stakeholders often have diverse and sometimes conflicting views.

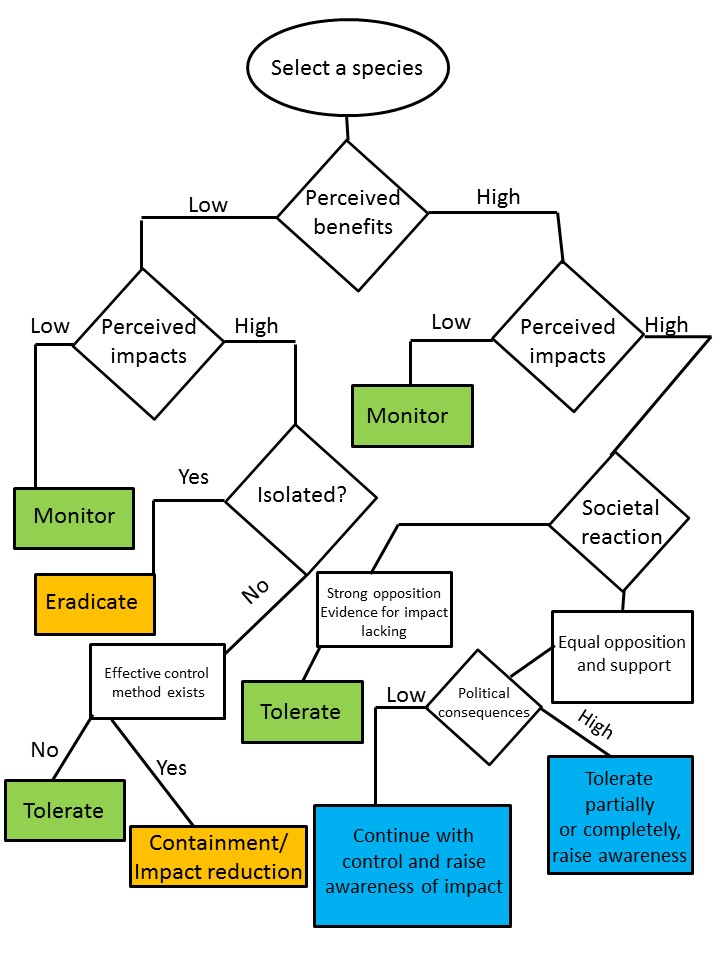

Until now, managers in cities have managed invasive species using approaches developed for rural areas, despite the different socio-environmental conditions in cities. “Managers of invasive species in cities need a framework for making decisions on how to best deal with individual species in a way that is acceptable and can deliver effective control”, says Gaertner.

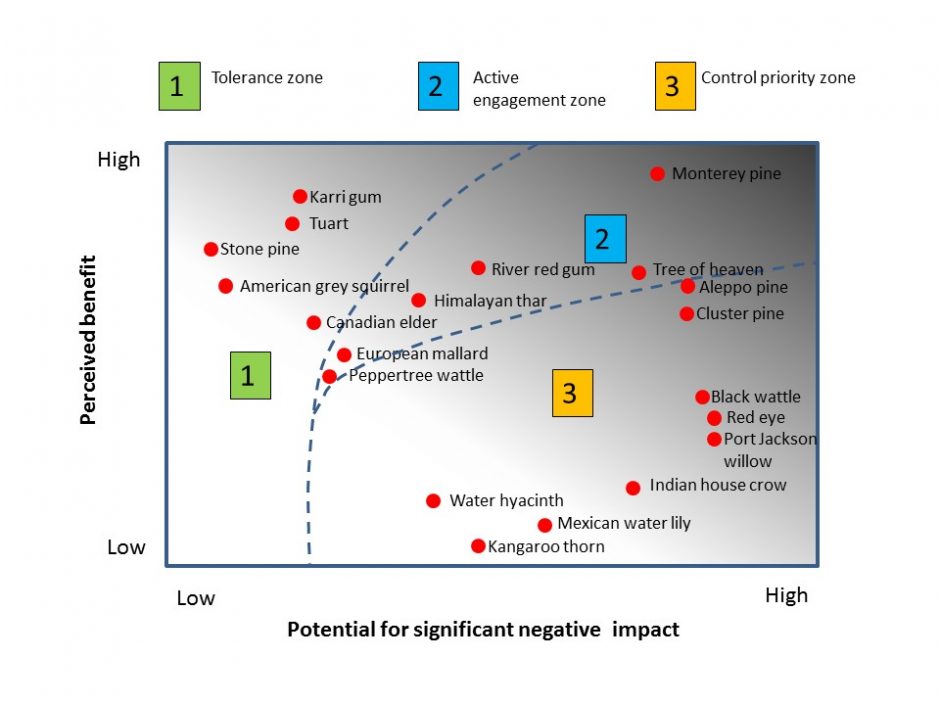

Gaertner and colleagues suggest selecting species according to their potential for causing impact (now and in the future) and the perceived value of the species. Depending on these factors, species can be grouped into three categories namely: (1) tolerance, (2) active engagement, (3) control priority.

The “tolerance” category is for species with high benefit and low impact for example, Karri gum (Eucalyptus diversicolor). Karri gum occurs in plantations in Table Mountain National Park that are popular with hikers, cyclists and tree enthusiasts. Perceived benefits are therefore high. Although these gumtrees impact water resources, they are not highly invasive (therefore a low impact).

“Active engagement” is for species that hold benefits but have negative impacts, for example, Monterey pine (Pinus radiata). Monterey pine are popular with hikers, cyclists and tree enthusiasts (high perceived benefit), but they are highly invasive and threaten the biodiversity of Table Mountain National Park (high impact).

The “control priority” category deals with species that have high impacts and low benefits, for example, most Australian Acacia species and some aquatic plant species, such as water hyacinth (Echhornia crassipes), has no benefits, is highly invasive and has major negative impacts.

Important conclusions from the study shows that stakeholder perceptions need to be given clear consideration and that management frameworks should allow for the acceptance of some invasive species.

“We may need to tolerate some invasive species for a combination of social and pragmatic reasons, however, we should look at ways to minimise potential negative effects” says Gaertner. She adds “The framework gives managers a much needed novel approach to tackling invasive species management in cities.”

Read the full paper in Landscape and Urban Planning

For more information, contact Mirijam Gaertner at gaertnem@sun.ac.za