21 June 2021 | By Mesfin Wondafrash

A recent paper, led by Dr Mesfin Gossa and published in Biodiversity and Conservation, reviews the value as well as the hazards associated with botanical gardens for biosecurity at a global scale.

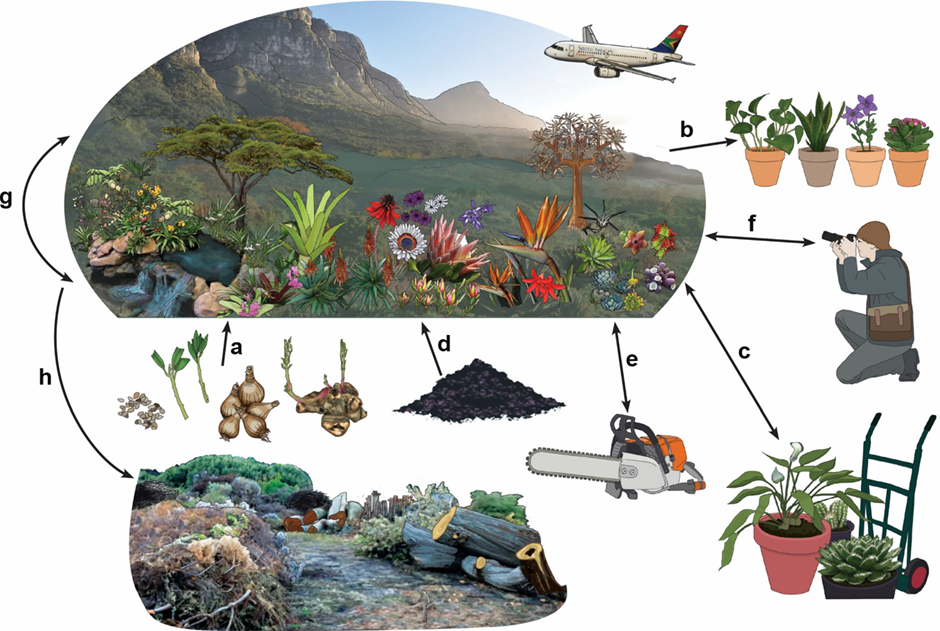

Globally there are over 3 000 botanical gardens. These gardens grow diverse collections of plants for conservation of plant biodiversity and aesthetic purposes. Historically, botanical gardens played a central role in sharing plants around the world, but this meant they were also a pathway for biological invasions. Moreover, as botanical gardens are often located close to high-risk sites for introduction of alien species, including seaports, airports, warehouses, depots and urban areas, they can be among the first locations where new invasions occur.

The paper highlights the role of botanical gardens in the detection and eradication of pest and pathogen invasions and in the determination of pest host range. It also emphasises their role as bridgeheads and conduits for biological invasions.

In his review, Mesfin and colleagues identified eight specific biosecurity hazards associated with botanical gardens and discussed the potential management interventions and the opportunities for improving biosecurity. The hazards are linked to regular activities of botanical gardens. These includes materials going into the gardens (planting materials, organic matter and soil), materials leaving the gardens (sold plants, prunings and dead plants), visits by local and international visitors, the use of machinery and equipment, plant exchange between botanical gardens and natural dispersal of pests and pathogens between managed estate of the gardens and the neighboring natural vegetation.

Dr Mesfin Gossa says, “Besides their value for plant biodiversity conservation, the diverse plant collections in botanical gardens can be used as valuable resources for pest and pathogen surveillance and monitoring. If used properly, botanical gardens can become champions of biosecurity and important hubs for plant health research.”

This is part of a postdoctoral research project initiated in South African botanical gardens in 2016, with the aim of detecting and identifying pest and pathogen risks by using botanical gardens as sentinel sites. The project was run by Dr Trudy Paap from 2016 to 2018 and by Dr Mesfin Gossa since 2019 under the leadership of Profs. Mike Wingfield, Bernard Slippers, Brett Hurley and Dr Trudy Paap from the Forestry and Agricultural Biotechnology Institute (FABI) of the University of Pretoria and Prof. John Wilson from the South African National Biodiversity Institute (SANBI) and a core-team member of the Centre of Invasion Biology (C∙I∙B). The project is funded by the Department of Forestry, Fisheries, and the Environment.

Read the paper in Biodiversity and Conservation:

Wondafrash M, Wingfield MJ, Wilson JRU, Hurley BP, Slippers B, Paap T. 2021. Botanical gardens as key resources for biosecurity. Biodiversity and Conservation. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-021-02180-0

For more information, contact Mesfin Wondafrash at Mesfin.Gossa@fabi.up.ac.za